Justice in Aging •

www.justiceinaging.org

• ISSUE BRIEF • 1

ISSUE BRIEF

Older Immigrants and Medicare

ISSUE BRIEF • APRIL 2019

Georgia Burke, Directing Attorney, Justice in Aging

Natalie Kean, Senior Staff Attorney, Justice in Aging

Table of Contents

Introduction .................................................... 1

Program Eligibility, Enrollment and Costs ...... 1

Paying for Coverage ....................................... 5

Summary of Eligibility and Premium

Assistance Options-LPR and TPS ................... 9

Post Enrollment Issues ................................... 9

Language Access and Medicare .................... 10

Conclusion ...................................................... 11

Endnotes ........................................................ 12

INTRODUCTION

Enrolling in the Medicare program and accessing

its benets can be complex and is often confusing for

older adults. e process can be even more challenging

for older immigrants, some of whom do not have a

signicant work history in the United States, are not

citizens, or have limited English prociency. Almost 7

million U.S. residents age 65 and older are immigrants,

and 4 million Medicare beneciaries are limited English

procient.

1

To assist advocates working with older immigrants

who may qualify for Medicare, this issue brief discusses

Medicare policies and practices most relevant to older

immigrants. Specically, it looks at:

• Eligibility and enrollment, with particular

attention to rules aecting non-citizens

• Help paying for coverage

• Post-enrollment issues potentially aecting

immigrant beneciaries

• Language access rights and resources in Medicare.

e issue brief includes numerous hypothetical

examples. e names and details are created to illustrate

the rules and are not actual case reports.

PROGRAM ELIGIBILITY,

ENROLLMENT AND COSTS

e Social Security Administration (SSA) determines

eligibility and handles enrollment for the two core

Medicare benets: Part A, generally referred to as the

hospital benet, and Part B, which covers physicians

and most other health services. Beneciaries with either

Part A or Part B coverage can enroll in Part D, the

prescription drug benet. e Centers for Medicare and

Medicaid Services (CMS) handles enrollment in Part

D, the prescription drug benet. Beneciaries with both

Part A and Part B coverage have the option to receive

their benets through managed care, called Medicare

Advantage. CMS is in charge of Medicare Advantage

enrollment.

2

Justice in Aging •

www.justiceinaging.org

• ISSUE BRIEF • 2

Premium costs for Medicare

Many older immigrants who immigrated later in life have little or no work history in the United States, a fact

that aects their Medicare costs, and, in some cases, their eligibility.

Part A premiums can be a particular challenge for some immigrants. Most Medicare beneciaries qualify

for Part A coverage without paying a premium. ey qualify based on their work credits (generally 40 quarters,

approximately ten years) or on the work credits of their spouse.

3

ose without the required credits must pay high

premiums for Part A coverage, up to $437/mo. in 2019.

4

Note that work credit requirements are dierent for people

qualifying for Medicare on the basis of disability and that there also are unique rules for people with ESRD.

In addition, Medicare Part B requires a premium payment, which for 2019 is $135.50/mo.

5

Both Part A and

Part B have late enrollment penalties that may apply to individuals who do not enroll when rst eligible.

6

Medicare

Prescription Drug Plans (PDPs) also have premiums that vary depending on the plan, as well as late enrollment

penalties for delays in enrollment.

To purchase Part A, an individual must also enroll in Part B. In contrast, it is possible to enroll only in Part B

and forgo Part A coverage. Individuals can enroll in the Part D prescription drug benet if they have either Part A or

Part B coverage.

Immigration status and enrollment

To enroll in either Part A or Part B, an individual must either be a U.S. citizen or be lawfully present in the

United States. In most cases, as discussed in detail below, a non-citizen who does not qualify for premium-free Part

A must be a lawful permanent resident (LPR) with ve years of continuous residence in the U.S. immediately prior

to Medicare enrollment.

Individuals who are not lawfully present (undocumented) are ineligible to receive any Medicare coverage under

any circumstances.

7

A. Citizens have no length of residency requirements

U.S. citizens face no length of residency requirement to enroll in Medicare, whether or not they have the work

credits to qualify for premium-free Part A.

8

ose who are living abroad and return to the U.S. after they reach

the age of 65, however, can face additional costs and gaps in enrollment if they do not enroll during the Initial

Enrollment Period (IEP) around their 65th birthday. In most cases, they do not have a Special Enrollment Period

(SEP) when they return so must wait until the General Enrollment Period (GEP), which extends from January 1

to March 31 each year, with coverage starting July 1. ey also face late enrollment penalties if they do not enroll

during their IEP, even though, when they are living abroad, they have no access to any Medicare benets.

Case Examples: Citizens living abroad

Mr. Santos, born in the Philippines, came to the United States twenty years ago. He worked and contributed to

Social Security and Medicare since shortly after he arrived. He has been a U.S. citizen for ten years but has lived in

the Philippines for the last four years caring for relatives, who are now deceased. He returned to the United States

in the fall last year, shortly after he turned 68. Because he is a U.S. citizen, he was able to begin his Part A Medicare

immediately. The fact that he reestablished U.S. residence only months ago was irrelevant to his eligibility for Part A

or Part B. Though eligible for Part B, he did however face a delay in enrolling. The fact that he was living overseas and

unable to use Medicare benets did not delay his IEP and there is no Special Enrollment Period for returning citizens.

He will only be able to enroll in Part B during the GEP with enrollment effective July 1. Mr. Santos will also owe a late

enrollment penalty for his Part B premium because he did not enroll during his IEP.

Justice in Aging •

www.justiceinaging.org

• ISSUE BRIEF • 3

Ms. Reyes, who will have her 65th birthday in a few months, came to the U.S. in the same year as Mr. Santos. She

also is a citizen and also spent extended periods out of the country to care for family members. She, however, does

not have the work history needed for premium-free Part A, but she wants to enroll and pay the premiums. Because

Ms. Reyes is a citizen, she can enroll in premium Part A during her IEP and in Part B without any length of residency

requirements. The Social Security Administration (SSA) will not look at her time abroad when processing her

enrollment.

B. Lawfully present non-citizens who qualify for Part A without a premium have no length

of residency requirement

Lawfully present individuals

9

with work credits that qualify them for premium-free Part A also do not face any

length of residency requirement.

10

is includes both LPRs and individuals in Temporary Protected Status (TPS)

who have sucient work credits. Because they qualify for premium-free Part A, these individuals can enroll in both

Part A and Part B without any length of residency requirement.

11

Although advocates for older adults report that they usually see only LPRs and TPS holders with the required

work history, it is possible that other categories of lawfully present individuals, such as Compact of Free Association

(COFA) Migrants or asylees, could accrue enough work credits to qualify for Part A without a premium. In many

cases, these would be younger individuals who qualify for disability-based Medicare with fewer years of work credits.

Case Examples: Lawfully present residents (LPR) with sufcient work credits for Part A

Ms. Morales, originally from El Salvador, has lived and worked in the United States for 13 years holding Temporary

Protected Status. Her work history qualies her for premium-free Part A. She can enroll in both Part A and Part B. The

fact that she is not an LPR will not be considered. It is sufcient that she is lawfully present.

Ms. Lopez is an LPR who came to the U.S. three years ago. She married another LPR shortly after arriving. Her

husband, a long-term U.S. resident, has enough credits for premium-free Part A. Ms. Lopez is turning 65. Because she

can rely on her husband’s work history, she can start her Part A and Part B coverage right away, even though she has

not been a U.S. resident for ve years.

Advocacy tip

Terminology can be confusing. For example SSA and CMS use the term “entitled to Part A benets” to describe

someone who qualies for premium-free Part A. Another possible point of confusion it the fact that, although

”Lawful Permanent Resident” (LPR) is the term used in most immigration contexts for green card holders (and also

used in this issue brief), SSA refers to those individuals as Lawfully Admitted Permanent Residents (LAPR).

C. Non-citizens without the work credits to qualify for premium-free Part A face additional

status and length of residency requirements

Many non-citizen immigrants do not have the work credits to qualify for premium-free Part A. To be eligible for

any Medicare benets, these individuals must 1) be lawful permanent residents (LPR, holding a green card) and 2)

have ve years of continuous residence in the United States immediately prior to Medicare enrollment.

12

e Social

Security Administration determines whether an individual has met the ve-year continuous residency requirements.

When does the ve-year period start? e ve-year period of U.S. residency begins the day the individual

arrives in the U.S. with the intention of establishing a home. e period can start before the individual has LPR

status. e ve-year clock can start, for example, with arrival under refugee or aslyee status. It cannot start with

visitor status since visitors are assumed to be retaining their foreign residence.

13

Justice in Aging •

www.justiceinaging.org

• ISSUE BRIEF • 4

What qualies as “continuing residence”? SSA looks at records of entry into the United States compiled by

the Department of Homeland Security.

14

Temporary absences do not aect “continuous” residence as long as the

individual intends to maintain U.S. residence, but if absences are frequent or of long duration, the agency may

inquire in order to determine whether continued U.S. residency was intended. Examples of evidence of intent could

include continuing to pay U.S. income taxes, maintaining a house or apartment with the individual’s furnishings

and belongings, etc. If an absence is over six months, SSA requires a “strong showing” of intent to retain U.S.

residence.

15

If SSA determines that continuous residence has been broken, the new ve-year period begins on the date that the

individual has returned to the United States.

Case Examples: LPRs without work credits

Mr. Rao, an LPR, came to the United States at age 62 to join the family of his son, a U.S. citizen. He has taken on a

little part-time work but mostly helps care for his grandchildren. Because he does not have enough work history in

the U.S. to qualify for premium-free Part A, Mr. Rao must wait for ve years from his date of entry to the U.S. to qualify

for any Medicare coverage. When he qualies he can enroll in premium Medicare Part A and Part B, or can decide to

enroll only in Part B.

Mr. Lee just turned 65. He has been an LPR since his arrival in the United States eight years ago but does not

have sufcient work history to qualify for Part A without a premium. Most years, he takes a trip back to Korea to visit

family, usually for about six weeks. Mr. Lee applied for Part B Medicare coverage. The Social Security Administration

accepted his application because he is an LPR and, despite several short absences, has met the continuous residency

requirements.

If an LPR subject to the ve-year continuous residency requirement marries someone with premium-free Part A

entitlement, the LPR, after a year of marriage, will also have Part A entitlement based on the spouse’s work history.

e continuous residency requirement will no longer apply.

16

Case Example: LPRs with work credits by marriage

Mr. Williams, a 65 year old LPR, came to the United States from Jamaica last year when he was 64. Because he is

subject to the ve-year continuous residency period, he cannot enroll in Medicare until he is 69. However, next month

he plans to marry Ms. Allen, also an LPR. She has been in the U.S. over 15 years and, because of her work history,

qualies for Part A without premiums. Once they are married for a year, Mr. Williams will be entitled to Part A without

premiums based on Ms. Allen’s record. He won’t have to wait for ve years to pass.

What about Medicare Part D and Part C (Medicare Advantage)? Part D and Part C do not have separate

citizenship or length of residency requirements. Plans are prohibited from requesting from a member any

documentation of citizenship or alien status. CMS provides the ocial status to the plan. If CMS records show that

a plan member is not lawfully present, the plan is required to disenroll the member.

17

Individuals with either Part

A or Part B can join a Part D plan. To join a Medicare Advantage plan under Part C, a beneciary must have both

Medicare Part A and Part B.

Advocacy tip

Enrollment denials or disenrollments arising from errors in SSA and/or CMS records will need to be corrected

with those agencies. ese denials are not subject to Medicare plan appeal processes.

Justice in Aging •

www.justiceinaging.org

• ISSUE BRIEF • 5

PAYING FOR COVERAGE

Even when an immigrant qualies for Medicare coverage, aording that coverage can be a challenge. is is

particularly true for immigrants who must pay premiums to enroll in the Part A benet. e steep Part A premiums

are simply out of reach for many. Premiums for Part B and Part D coverage also add to the nancial burden for

low-income immigrants.

State Medicaid programs can assist with Medicare premiums

ere are several ways that state Medicaid programs can assist low-income immigrants with Medicare costs.

Every state’s standard Aged and Disabled (A&D) Medicaid benet includes payment of the Part B premium for

Medicare beneciaries. e income and asset limits for A&D Medicaid, though they vary by state, are low.

Medicare Savings Programs (MSPs) operated by state Medicaid agencies also oer premium relief and generally

have higher income and asset limits. MSPs do not provide full Medicaid coverage; instead they are specically

designed to assist with Medicare aordability. Federal law sets minimum countable income and asset limits for

MSPs that are higher than for A&D Medicaid, and states have the option to be more generous than federal law

requires. e National Council on Aging (NCOA) has created a chart showing each state’s requirements.

18

e MSP with the richest program benets, the Qualied Medicare Beneciary (QMB) program, can be

particularly helpful to low-income immigrants who must pay a premium for Part A. Under the QMB program, the

state Medicaid agency pays both Part A and Part B premiums. In most states, income must be at or below 100%

of the federal poverty level (FPL) and countable resources may not exceed (for 2019) $7,730 for an individual and

$11,600 for a couple. As the NCOA chart shows, some states have raised income and/or asset cut-os signicantly

and a few have abolished the asset test altogether.

19

In addition to paying Medicare premiums, QMB enrollment protects beneciaries from paying Medicare

deductibles and co-insurance. Note that many QMBs also qualify for A&D Medicaid and are referred to as QMB-

plus.

Two other MSP programs, the Specied Low-income Medicare Beneciary (SLMB) program and the Qualied

Individual (QI) program, only pay Part B premiums. e federal minimum income requirements for these programs

are 135% of FPL and 150%, respectively. Minimum asset requirements for both programs are the same as for the

QMB benet.

State Medicaid programs, including MSPs, have immigration status and length of residency requirements.

20

For

A&D Medicaid and MSPs, individuals must be “qualied” (a status that includes LPR but not TPS). Most qualied

immigrants, including LPRs, are subject to a ve-year bar before qualifying for Medicaid benets. ese restrictions

mean that a Medicare-eligible individual with TPS cannot get help from Medicaid with Part B premiums or

co-insurance. e ve-year bar can also aect Medicaid eligibility for some LPRs.

Advocacy tip

Advocates report that many immigrant families are reluctant to apply for any needed Medicaid benet for older

family members because of fears of estate recovery. It is important to inform beneciaries and their families that the

QMB benet and other MSPs are exempt from estate recovery.

Justice in Aging •

www.justiceinaging.org

• ISSUE BRIEF • 6

Case Examples: Medicare Savings Programs

Ms. Morales, a TPS holder, has Medicare Part A coverage because of her long work history in the U.S. Her income

is below 100% of FPL but she cannot qualify for QMB assistance with her Part B premiums because she is not in

“qualied” status.

Ms. Gonzales, an LPR, gets Part A without paying a premium based on her husband’s work history. Her income and

assets qualify her for the SLMB benet but she only has three years of continuous residence in the U.S. She will have

to wait another two years before she can enroll in SLMB to get help with her Part B premiums.

Enrolling in the QMB program can be challenging

As discussed above, the QMB benet can be particularly helpful to low-income immigrants who must pay a

premium for Part A. e mechanics and timing of enrolling in the QMB program, however, can be complex.

Enrollment procedures depend on the state and on whether the individual already is enrolled in Part B. For those

who are not enrolled in Part B and/or who are in “group payer states” as discussed below, enrollment may require

visits to both the Social Security oce to apply for “conditional” Part A enrollment, and to the state Medicaid

agency to apply for QMB enrollment.

In the majority of states (identied as “Part A buy-in states”), individuals can apply for QMB coverage at any time

of the year and coverage begins in the month immediately following approval. In 14 states (identied as “group payer

states”), however, people without premium-free Part A may only apply at SSA for conditional Part A enrollment

during the General Enrollment Period (January 1-March 31) each year,

21

with QMB enrollment beginning no

earlier than July 1.

A Justice in Aging fact sheet

22

and recently-issued clarifying guidance from SSA detail the specic steps needed to

apply in each set of states.

23

Advocacy tip

Advocates should give their clients step-by-step guidance so that they follow through with all needed procedures.

Particularly in group payer states, calendared reminders and follow-up may be needed to ensure that clients

successfully navigate the enrollment process.

Case Example: Enrolling in QMB

Mrs. Chen is 66 and lives in Arizona, a group payer state. She came to the U.S. seven years ago and has met the

status and residency requirements to qualify for Medicare. Since she has no work history, she has not enrolled in

Medicare because she cannot pay the premiums, especially the Part A premium, which tops $440/mo. In June, she

meets with an advocate who tells Mrs. Chen that, with her income and assets, she qualies for the QMB program,

which will pay both her Part A and Part B premiums. She tells Mrs. Chen, however, that she must wait until January to

go to SSA and apply for conditional Part A enrollment and for Part B. With Mrs. Chen’s consent, the advocate also

tells her daughter and urges both of them to put the date on their calendars. In December, the advocate contacts

both Mrs. Chen and her daughter to remind them to make an appointment with SSA in January and, after applying for

conditional enrollment at SSA, to go directly to the state Medicaid ofce to apply for QMB. The advocate follows up

in late January to make sure that Mrs. Chen took the required steps. She did, and nally on July 1, to her great relief,

Mrs. Chen gets both Part A and Part B coverage without premiums. Mrs. Chen, because of her QMB status, is also

protected from payment of co-insurance and deductibles.Her QMB enrollment also automatically qualies her for the

Part D Low-income Subsidy (discussed below) to help her with prescription drug co-insurance.

Justice in Aging •

www.justiceinaging.org

• ISSUE BRIEF • 7

Marketplace enrollment offers an alternate coverage option

Immigrants who do not qualify for premium-free Part A can also consider enrolling in a Qualied Health Plan

(QHP) in the Marketplace and applying for nancial assistance in the form of premium tax credits and cost-sharing

reductions.

QHPs are available to LPRs as well as individuals on non-immigrant visas and with other status, including many

temporary status categories.

24

Immigrants who are eligible to enroll in QHPs and do not have other “minimum

essential coverage” may also qualify for premium tax credits and cost-sharing reductions to help them aord

coverage.

25

ere are no length of residency requirements for QHPs or for premium tax credits and cost-sharing

reductions. Further, lawfully present individuals, unlike citizens, can receive premium tax credits and cost

sharing reductions, even if their income is below 100% of FPL if they are ineligible for Medicaid because of their

immigration status.

26

When sorting through beneciary eligibility and enrollment options, it is important to remember that, though

there are signicant variations among the states, QMB income counting rules are grounded on SSI income counting

rules. In contrast, Marketplace rules on premium tax credits and cost-sharing reductions apply Modied Adjusted

Gross Income (MAGI) rules.

27

Depending on an individual’s income and circumstances, getting coverage through the Marketplace may be less

expensive than paying for Part A. ose who choose Marketplace coverage rather than Medicare need to be aware

that, if they later decide to switch to Medicare, they can face late enrollment penalties for both Part A and Part B.

28

ey also may face gaps in coverage because they may only be able to enroll in Medicare during the annual General

Enrollment Period.

29

Because of the range of visa and status categories for which Marketplace enrollment is permitted and because

there is no length of residency requirement, the Marketplace also is an option for older adults who do not currently

qualify for Medicare at all, including LPRs who are still in their ve-year waiting period.

Advocacy tip

Advocates should remind clients choosing Marketplace coverage that, even if their income is below tax ling

requirements, they need to le income tax returns in order to get MAGI-based subsidies.

Case Examples: Marketplace and Medicare

Ms. Park is an LPR who is eligible for Medicare but does not qualify for premium-free Part A. Her income is at 200%

FPL, which is too high to qualify for the QMB program in her state. Because her income is low enough to qualify her

for premium tax credits and cost-sharing reductions in the Marketplace, she decides to enroll in a Qualied Health

Plan. She will face both Part A and Part B enrollment penalties if she later decides to enroll in Medicare and will only

be able to do so during certain times of year.

Mr. Jones is an LPR who arrived in the U. S. when he was 62. He is now 66 and enrolled in a Marketplace plan with

premium tax credits and cost-sharing reductions. Next year he will have been in the U.S. for ve years. At that time he

will become eligible for Medicare and, because of his low income, he will also qualify for his state’s Medicaid program.

He will lose his eligibility for Marketplace subsidies so he will switch from the Marketplace to Medicare. His Medicaid

coverage will assist with his Medicare costs.

Justice in Aging •

www.justiceinaging.org

• ISSUE BRIEF • 8

Some people choose to enroll only in Part B

Enrolling only in Medicare Part B and not in Part A is an available option for people who face steep Part A

premiums but don’t qualify for either subsidies for Marketplace coverage or QMB assistance for Medicare premiums.

Part B enrollment allows them to also enroll in Part D and, if they qualify, to get the Low-Income Subsidy (LIS) to

help pay for Part D costs (see below). is course is far from ideal because it leaves an individual without coverage

for hospital costs. However, it is an available option. If these individuals later decide to enroll in Part A, they can face

late enrollment penalties and also may be limited to enrolling during the General Enrollment Period with coverage

not starting until July. If they enroll in Part B and not in Part D, they could also face Part D late enrollment

penalties.

Case Example: Declining Part A coverage

Mr. Singh came to the U.S. eight years ago. He is now 65, LPR and eligible for Medicare but not for premium-free

Part A. From his career in India, he has a pension and a small nest egg, disqualifying him for Medicaid or Marketplace

subsidies. Because has always been healthy, he decides to conserve resources and only enroll in Part B and not in

Part A. By doing so, he will have coverage for doctor visits but risks wiping out his nest egg if he needs hospital care.

Though he currently only takes one inexpensive generic drug, he enrolls in a low cost Part D plan so that he will not

face late enrollment penalties if he later nds that his drug coverage needs increase.

The Part D Low Income Subsidy (“Extra Help”) can reduce prescription drug costs

Beneciaries who qualify for Part D, i.e., those who are enrolled in either Part A or Part B, also may be eligible

for the Part D Low Income Subsidy (LIS or “Extra Help”).

30

Because LIS asset and income limits are higher than

those for QMB and other Medicare Savings Programs, some individuals with higher incomes may qualify for this

benet. e Social Security Administration determines LIS eligibility. Individuals may apply with SSA in-person,

on-line or by phone.

ere are no additional immigration status or length of U.S. residency requirements for LIS beyond what is

needed for Part A and Part B eligibility.

31

LIS enrollment is automatic for Medicare beneciaries receiving SSI and

for those enrolled in any Medicaid program, including Medicare Savings Programs such as the QMB program.

Others can apply by contacting the Social Security Administration and meeting income and asset eligibility

requirements.

32

Instructions for applying are available in 18 languages.

33

Case Example: Extra Help v. QMB

Ms. Morales, a low-income TPS holder with premium-free Part A, successfully applied for the Part D Low Income

Subsidy. Although she had been unable to enroll in the QMB program because she was not a “qualied” immigrant,

that was not a factor in evaluation her LIS application. Having LIS gives her with signicant relief from prescription

drug costs.

Policy Watch

In 2018, the Department of Homeland Security proposed new regulations that would treat receipt of the

LIS benet as a factor in determining whether an applicant for LPR status would likely be a public charge.

34

As

proposed, the changes would be prospective and not aect current LIS enrollees. Advocates will want to monitor the

progress of this proposal.

35

Justice in Aging •

www.justiceinaging.org

• ISSUE BRIEF • 9

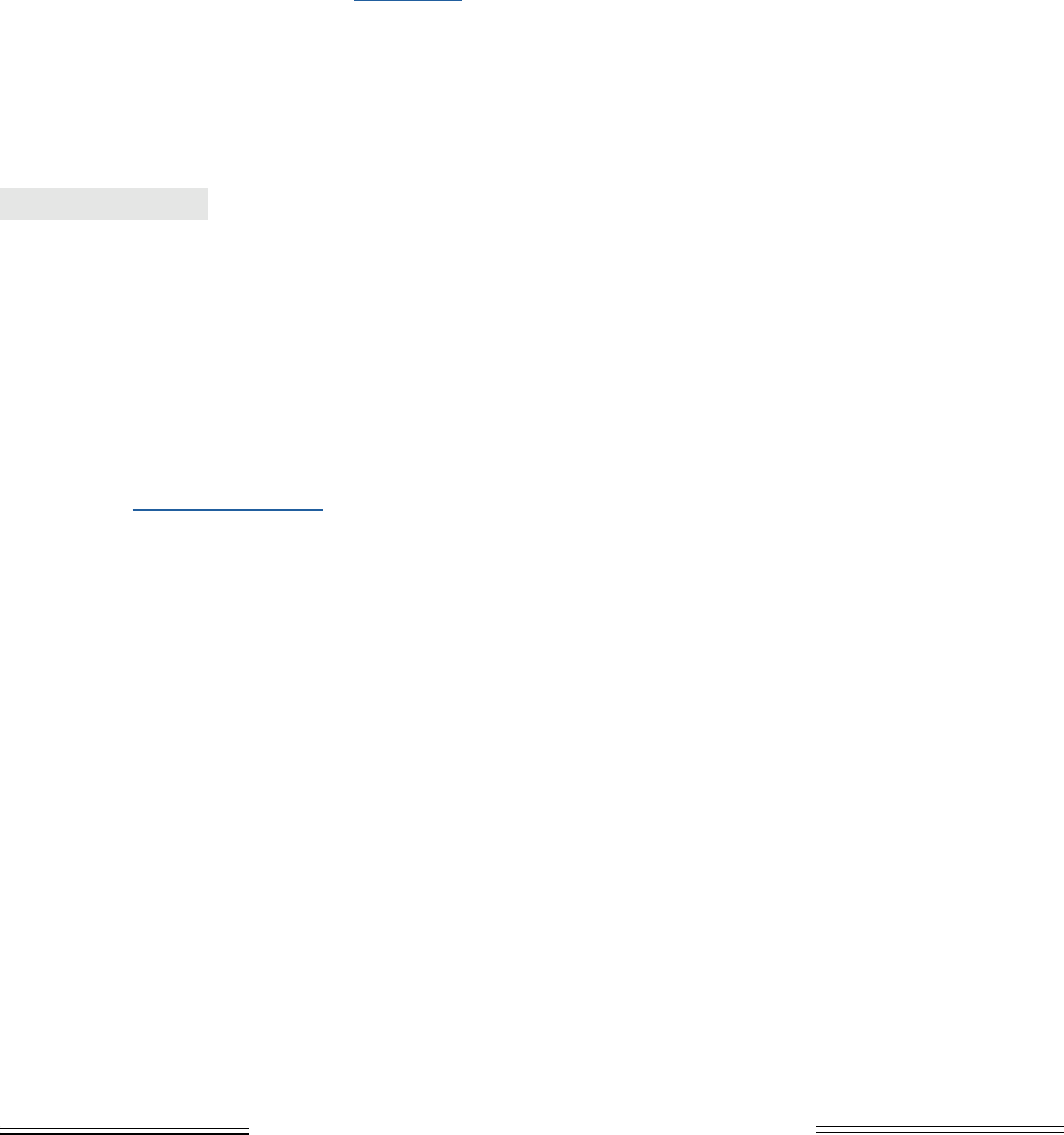

SUMMARY OF ELIGIBILITY AND PREMIUM ASSISTANCE

OPTIONS—LPR AND TPS

MEDICARE

ELIGIBILITY

AVAILABLE PROGRAMS TO HELP W/ COSTS

Does 5 yr.

residence apply?

Medicaid and MSPs Part D LIS

Are Marketplace

subsidies available?

LPR—qualifying

work record

No

Yes w/ 5 yr

residence

Yes No

LPR –w/out

qualifying work

record

Yes but w/ Part A

premium

Yes w/ 5 yr.

residence

Yes if enroll in

either A or B

Yes*

TPS—qualifying

work record

No No Yes No

TPS-w/out

qualifying work

record

No N/A N/A

Yes

*For those with income below 100% FPL, subsidies are available only if they cannot qualify for Medicaid because of

their immigration status.

POST ENROLLMENT ISSUES

Medicare does not pay for services outside the U.S.

Many immigrants, particularly those who are citizens, may spend signicant time overseas during their

retirement. Medicare does not cover health care provided outside the United States.

36

Medicare premium payment liabilities continue even when a beneciary is abroad.

e obligation to continue payment of Medicare premiums continues when a beneciary spends time abroad. If a

beneciary stops paying Part A or Part B premiums, late enrollment penalties can arise and the beneciary may have

to wait until the next Medicare General Enrollment Period to reapply, resulting in many months without coverage.

Beneciaries who have Medicare coverage and spend time abroad should be careful about how they handle their

Medicare premiums.

Case Example: Time abroad

Ms. Adebayo, originally from Nigeria, is a U.S. citizen with Medicare Part A and Part B coverage. She rushed back

to Nigeria after a niece died suddenly, leaving several small children. She now realizes that she is needed for an

indenite time to make sure that the children are properly cared for. Though she has the option of stopping her Part B

premiums, she decides that she will let SSA continue to deduct the premium from her monthly Social Security benet.

She does not want to face late enrollment penalties when she returns or have a gap in coverage while she waits for an

enrollment period to re-enroll.

Justice in Aging •

www.justiceinaging.org

• ISSUE BRIEF • 10

LANGUAGE ACCESS AND MEDICARE

Older immigrants with limited English prociency need language assistance to understand their benets, address

their health care needs, and exercise their rights under Medicare.

Governing statutes

e statutory bases for language access rights in Medicare are found in Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

37

and the Health Care Rights Law, Section 1557 of the Aordable Care Act.

38

Section 1557 applies the provisions

of Title VI to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and to health programs and activities, any

part of which receive Federal nancial assistance from HHS. e HHS Oce for Civil Rights has enforcement

responsibility. In addition, Section 1557 provides for a private right of action.

39

HHS takes the position that those physicians and other providers who participate in Medicare only as Part B

providers and do not receive any other Federal nancial assistance from HHS are not subject to Section 1557, but

asserts that almost all physicians in fact are covered because they accept Federal nancial assistance from sources

other than Medicare Part B.

40

Regulations and guidance

e HHS Oce for Civil Rights and CMS have each adopted regulations implementing these statutes. CMS has

also developed sub-regulatory guidance for Medicare Advantage plans and Prescription Drug Plans. CMS has noted,

however, that plan and provider obligations under the statutes may be broader than the specic requirements in its

guidance and advises plans to independently assess their obligations under these statutes.

HHS regulations require free, accurate, and timely language assistance when needed to provide meaningful

access to individuals with limited English prociency.

41

e HHS regulations do not identify specic instances

where interpreter services are required or specic documents that must be translated, but, in commentary, the

agency provides guidance on factors to be considered in enforcement.

42

Interpreter and translation services must be

provided by “qualied” interpreters and translators.

43

Covered entities may not require that individuals provide their

own interpreters and may not use a minor child except in cases of emergency.

44

Medicare plans also are required to

include taglines with “signicant” documents and communications. e tagline must provide information in the top

15 languages of the state announcing the availability of language services.

45

Medicare regulations governing health and prescription drug plans include additional specic requirements.

ey require that Medicare Advantage and Medicare Prescription Drug Plans must translate “vital materials” into

any non-English language that is the primary language of at least ve percent of the individuals in a plan benet

package service area.

46

In the Medicare Communications and Marketing Guidance (MCMG), CMS identies vital

documents as including most basic marketing materials (application, evidence of coverage and summary of benets,

provider and drug lists, etc.); enrollment and disenrollment communications; and appeals and grievance notices.

47

Except for a few Medicare Advantage plan service areas, the ve percent threshold means that Spanish is the only

language required.

Advocacy Tip

If clients are in Medicare Advantage plans are having problems getting needed interpreter services, the most

expeditious route to getting individual issues addressed is likely to be ling a grievance with the plan and/or a

complaint with CMS at 1-800-Medicare.

Justice in Aging •

www.justiceinaging.org

• ISSUE BRIEF • 11

MCMG also requires plan call centers to have interpreter services in all languages.

48

Wait times should not be

excessive.

Agency resources

e Medicare consumer website, Medicare.gov, is available in Spanish.

49

e Medicare & You Handbook is

also published in Spanish. An “Information in Other Languages” page

50

lists all non-English language forms and

publications available from CMS. e 1-800-Medicare help line provides free interpretation services in all languages

and, as noted above, all call centers for Medicare Part D plans and Medicare Advantage plans are required to do so

as well.

51

e Marketplace website, HealthCare.gov, also is available in Spanish. HealthCare.gov has non-English resources

as well.

52

e Marketplace Call Center and QHPs are also required to provide interpretation services.

53

Advocacy Tip

CMS data show that very few individuals who speak languages other than Spanish ask for interpreter services

when calling 1-800-Medicare. Plan level data are not available, but it appears that uptake there as well is limited.

is suggests that LEP individuals are either unaware of the free service or reluctant to ask for it. Advocates should

explain the availability of these services to their clients and encourage their use when they have questions or if they

receive a document from Medicare or from their MA plan in English that they do not understand.

CONCLUSION

Advocates can assist their older immigrant clients to navigate Medicare enrollment, costs, and language hurdles.

Justice in Aging is available to work with advocates as they encounter Medicare issues for their immigrant clients.

Contact info@justiceinaging.org.

We would like to acknowledge and thank Nancy Lorenz of Greater Boston Legal Services and Vicky Pulos of

Massachusetts Law Reform Institute for their valuable contributions to this report.

Justice in Aging •

www.justiceinaging.org

• ISSUE BRIEF • 12

ENDNOTES

1 Migration Policy Institute, “State Immigration Data Proles, United States,” available at www.migrationpolicy.org/data/state-pro-

les/state/demographics/US; CMS Oce of Minority Health, “Understanding Communication and Language Needs of Medicare

Beneciaries,” 8, 10 (Apr 2017), available at www.cms.gov/About-CMS/Agency-Information/OMH/Downloads/Issue-Briefs-Under-

standing-Communication-and-Language-Needs-of-Medicare-Beneciaries.pdf.

2 For a description of the parts of Medicare and services covered, see CMS “Medicare & You” (2019), available at www.medicare.gov/

forms-help-resources/medicare-you-handbook/download-medicare-you-in-dierent-formats.

3 42 C.F.R. § 406.10. See also 42 C.F.R. § 406.12 which applies to individuals who qualify for premium-free Part A based on

disability determination by the Social Security Administration, and 42 C.F.R. § 406.13, which applies to individuals with ESRD.

See CMS, “Original Medicare (Part A and B) Eligibility and Enrollment,” available at www.cms.gov/Medicare/Eligibility-and-En-

rollment/OrigMedicarePartABEligEnrol/. e POMS provisions concerning Part A entitlement are found at subchapter HI 00801,

available at https://secure.ssa.gov/apps10/poms.nsf/subchapterlist!openview&restricttocategory=06008.

4 SSA requires fewer work credits for individuals under 65 who qualify for Medicare on the basis of disability, using a formula based

on the applicant’s age when becoming disabled. For a chart of credits needed based on age, see SSA, “How You Earn Credits” (2019),

p. 3, available at www.ssa.gov/pubs/EN-05-10072.pdf.

5 CMS, “Medicare costs at a glance,” available at www.medicare.gov/your-medicare-costs/medicare-costs-at-a-glance.

6 For a summary of late enrollment penalties, see www.mymedicarematters.org/enrollment/penalties-and-risks/. To calculate late

enrollment penalties see www.medicareinteractive.org/get-answers/medicare-health-coverage-options/original-medicare-enrollment/

medicare-part-b-late-enrollment-penalties.

7 e SSA POMS GN 00303.800 has created some confusion about whether this prohibition applies to undocumented persons with

ESRD. e POMS provision notes that there are no residency, citizenship or alien status requirements for Medicare entitlement

based on ESRD. Entitlement, however, must be distinguished from actually access to the benet. Pursuant to the Personal Respon-

sibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA), no Medicare payments can be made for an undocumented

beneciary. See SSA POMS RS 00204.010(B), available at https://secure.ssa.gov/apps10/poms.nsf/lnx/0300204010. us, as with

other Medicare benets, ESRD-based Medicare is only available to those non-citizens who are lawfully present.

8 42 C.F.R. § 406.20.

9 For the denition of lawfully present for purposes of SSA benets as well as Medicare determinations, see 8 C.F.R. § 1.3 and SSA

POMS RS 00204.00 available at https://secure.ssa.gov/apps10/poms.nsf/lnx/0300204010.

10 42 U.S.C § 1395o; 42 C.F.R. § 406.10 (a)(1).

11 42 U.S.C. § 1395o; 42 C.F.R §§406.10 and 407.10(a)(1).

12 For Part A, these restrictions are found at 42 U.S.C. § 1395i-2(a)(3) and 42 C.F.R. § 406.20. e restrictions for Part B are found at

42 U.S.C. § 1395o(2) and 42 C.F.R § 407.10(a)(2).

13 SSA POMS GN 00303.800(B)(4), available at https://secure.ssa.gov/apps10/poms.nsf/lnx/0200303800.

14 Id.

15 Id. See also SSA POMS GN 00303.740 describing SSA procedures to determine residence, available at https://secure.ssa.gov/apps10/

poms.nsf/lnx/0200303800.

16 SSA POMS GN 00303.800(A)(2), available at https://secure.ssa.gov/apps10/poms.nsf/lnx/0200303800.

17 Medicare Managed Care Manual, Ch. 2, at 50.2.7, available at www.cms.gov/Medicare/Eligibility-and-Enrollment/MedicareMang-

CareEligEnrol/Downloads/CY_2019_MA_Enrollment_and_Disenrollment_Guidance.pdf.

18 See NCOA, Chart: Medicare Savings Programs: Eligibility and Coverage, available at www.ncoa.org/wp-content/uploads/medi-

care-savings-programs-coverage-and-eligibility.pdf.

Justice in Aging •

www.justiceinaging.org

• ISSUE BRIEF • 13

19 Id.

20 See CMS, “Eligibility for Non-Citizens in Medicaid and CHIP” (Nov. 2014), available at www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/out-

reach-and-enrollment/downloads/overview-of-eligibility-for-non-citizens-in-medicaid-and-chip.pdf.

21 ese states, called “Group Payer” states, are: AL, AZ, CA, CO, IL, KS, KY, MO, NE, NJ, NM, SC, UT, and VA.

22 Justice in Aging, “SSA Claries Handling of Medicare Part A Conditional Applications,” available at www.justiceinaging.org/

wp-content/uploads/2018/08/SSA-Claries-Handling-of-Medicare-Part-A-Conditional-Applications.pdf.

23 SSA POMS, HI 00801.140, available at https://secure.ssa.gov/poms.nsf/lnx/0600801140.

24 See “Immigration status and the Marketplace,” available at www.healthcare.gov/immigrants/immigration-status/. For additional de-

tail see NILC, “’Lawfully Present’ Individuals Eligible under the Aordable Care Act,” available at www.nilc.org/issues/health-care/

lawfullypresent/.

25 Ctr. on Budget & Policy Priorities, “Key Facts: Immigrant Eligibility for Health Insurance Aordability Programs,” (2015), available

at www.healthreformbeyondthebasics.org/key-facts-immigrant-eligibility-for-coverage-programs/.

26 26 U.S.C. § 36B(c)(B). See also HealthCare.gov “Coverage for lawfully present immigrants,” available at https://www.healthcare.

gov/immigrants/lawfully-present-immigrants/.

27 For a primer of MAGI counting rules, see Nat’l Health Law Program, “Advocate’s Guide to MAGI,” available at https://healthlaw.

org/resource/advocates-guide-to-magi-updated-guide-for-2018/.

28 If they don’t enroll in either Part A or Part B, they would not face Part D late enrollment penalties. Late enrollment calculations

are only triggered after the individual becomes eligible for Part D. Part D requires either Part A or Part B coverage. See 42 C.F.R. §

423.38 and 423.46.

29 CMS has created a Medicare-Medicaid Master FAQ that discusses the details of interaction between Medicare and Marketplace

coverage, available at www.cms.gov/Medicare/Eligibility-and-Enrollment/Medicare-and-the-Marketplace/Overview1.html. See

especially Questions A.6, A.8 and A.9.

30 See www.ssa.gov/benets/medicare/prescriptionhelp/.

31 HHS has not determined the Low Income Subsidy to be a federal “public benet.”See ASPE, “Summary of Immigrant Eligibility Re-

strictions Under Current Law,” available at https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/summary-immigrant-eligibility-restrictions-under-cur-

rent-law. us eligibility is not limited to “qualied” immigrants.

32 See SSA Extra Help webpage at www.ssa.gov/benets/medicare/prescriptionhelp/ for information on the program and links to ap-

plication forms. For details of eligibility and benet levels, see also a helpful chart from the National Council on Aging, available at

www.ncoa.org/wp-content/uploads/part-d-lis-eligibility-and-benets-chart.pdf.

33 See SSA, “Extra Help Information in Other Languages,” available at www.ssa.gov/benets/medicare/prescriptionhelp/other-languag-

es.html.

34 For an overview of the impact of the public charge proposal on older adults, see Justice in Aging, “Public Charge: A reat to the

Health & Well-being of Older Adults in Immigrant Families,” (Oct. 2018), available at www.justiceinaging.org/wp-content/up-

loads/2018/09/Public-Charge_A-reat-to-the-Health-Wellbeing-of-Older-Adults-in-Immigrant-Families.pdf.

35 Justice in Aging will alert its network to any signicant developments. Another good source of information is the Protecting Immi-

grant Families website, available at https://protectingimmigrantfamilies.org/about-us-2/.

36 ere are minor exceptions for people in transit between the continental U.S. and Alaska and for emergency use of a hospital across

the border that is closer than the nearest U.S. facility.

37 42 U.S.C. § 2000d et seq.

38 42 U.S.C. § 18116.

Justice in Aging •

www.justiceinaging.org

• ISSUE BRIEF • 14

39 45 C.F.R. § 92.301. See also discussion at 81 Fed. Reg. 31376, 31439-40 (May 18, 2016)(hereinafter “Final Rule”), available at www.

govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2016-05-18/pdf/2016-11458.pdf.

40 See discussion at 80 Fed. Reg. 54172, 54195 (Sept. 8, 2015), available at www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2015-09-08/pdf/2015-

22043.pdf and Final Rule at 31383, supra note 24.

41 45 C.F.R. § 92.201 (a) and (c).

42 See Final Rule at 31416, supra note 41.

43 e denition of qualied interpreter and qualied translator are found at 45 C.F.R. § 92.4.

44 45 C.F.R. § 92.201(e). See also commentary at Final Rule 31417-18, supra note 41.

45 45 C.F.R. § 92.8. Note however that a joint Report to the President by HHS, the Department of the Treasury and the Department

of Labor recommended scaling back the regulation requiring inserts, asserting that the requirement is costly and wasteful. See “Re-

forming America’s Healthcare System rough Choice and Competition,” p. 75, available at www.hhs.gov/sites/default/les/Reform-

ing-Americas-HealthCommunications and Marketing Guidelines-System-rough-Choice-and-Competition.pdf.

46 42 C.F.R. § 422.2268(a)(7) and 42 C.F.R. § 423.2268(a)(7).

47 e full list of communications subject to translation requirements is found at MCMG at 100.4, available at www.cms.gov/Medi-

care/Health-Plans/ManagedCareMarketing/CY2019_Medicare_Communications_and_Marketing_Guidelines.pdf. at list is

eective as of January 1, 2019.

48 Id. at 30.3.

49 https://es.medicare.gov/.

50 www.medicare.gov/about-us/other-languages/information-in-other-languages.html.

51 MCMG, supra note 49 at 30.3, available at www.cms.gov/Medicare/Health-Plans/ManagedCareMarketing/CY2019_Medicare_

Communications_and_Marketing_Guidelines.pdf.

52 www.healthcare.gov/language-resource/.

53 45 C.F.R. § 155.205(c).