ESG AND FINANCIAL

PERFORMANCE:

Uncovering the Relationship by

Aggregating Evidence from 1,000 Plus

Studies Published between 2015 – 2020

By Tensie Whelan, Ulrich Atz, Tracy Van Holt and Casey Clark, CFA

2 ESG and Financial Performance

Meta-studies examining the relationship between ESG and financial performance have a decades-long

history. Almost all the articles they cover, however, were written before 2015. Those analyses found positive

correlations between ESG performance and operational eciencies, stock performance and lower cost of

capital. Five years later, we have seen an exponential growth in ESG and impact investing – due in large

part to increasing evidence that business strategy focused on material ESG issues is synonymous with high

quality management teams and improved returns. A case in point: A recent study looked at the initial stock

market reaction to the COVID-19 crisis (up to March 23) and found that companies scoring high on a “crisis

response” measure (based on Human Capital, Supply Chain, and Products and Services ESG sentiment) were

associated with 1.4-2.7% higher stock returns (Cheema-Fox et al., 2020). Nevertheless, the topic continues to

be debated, with some arguing that companies and investors should stick to managing for stock price and

that ESG is, at best, a distraction from the real business of making money.

The authors of this report, NYU Stern Center for Sustainable Business and Rockefeller Asset Management,

collaborated to examine the relationship between ESG and financial performance in more than 1,000

research papers from 2015 – 2020. Because of the varying research frameworks, metrics and definitions,

we decided to take a dierent approach than previous meta-analyses. We divided the articles into

those focused on corporate financial performance (e.g. operating metrics such as ROE or ROA or stock

performance for a company or group of companies) and those focused on investment performance (from

the perspective of an investor, generally measures of alpha or metrics such as the Sharpe ratio on a portfolio

of stocks), to determine if there was a dierence in the findings. We also separately reviewed papers and

articles focused on low carbon strategies tied to financial performance in order to understand financial

performance implications through the lens of a single thematic issue.

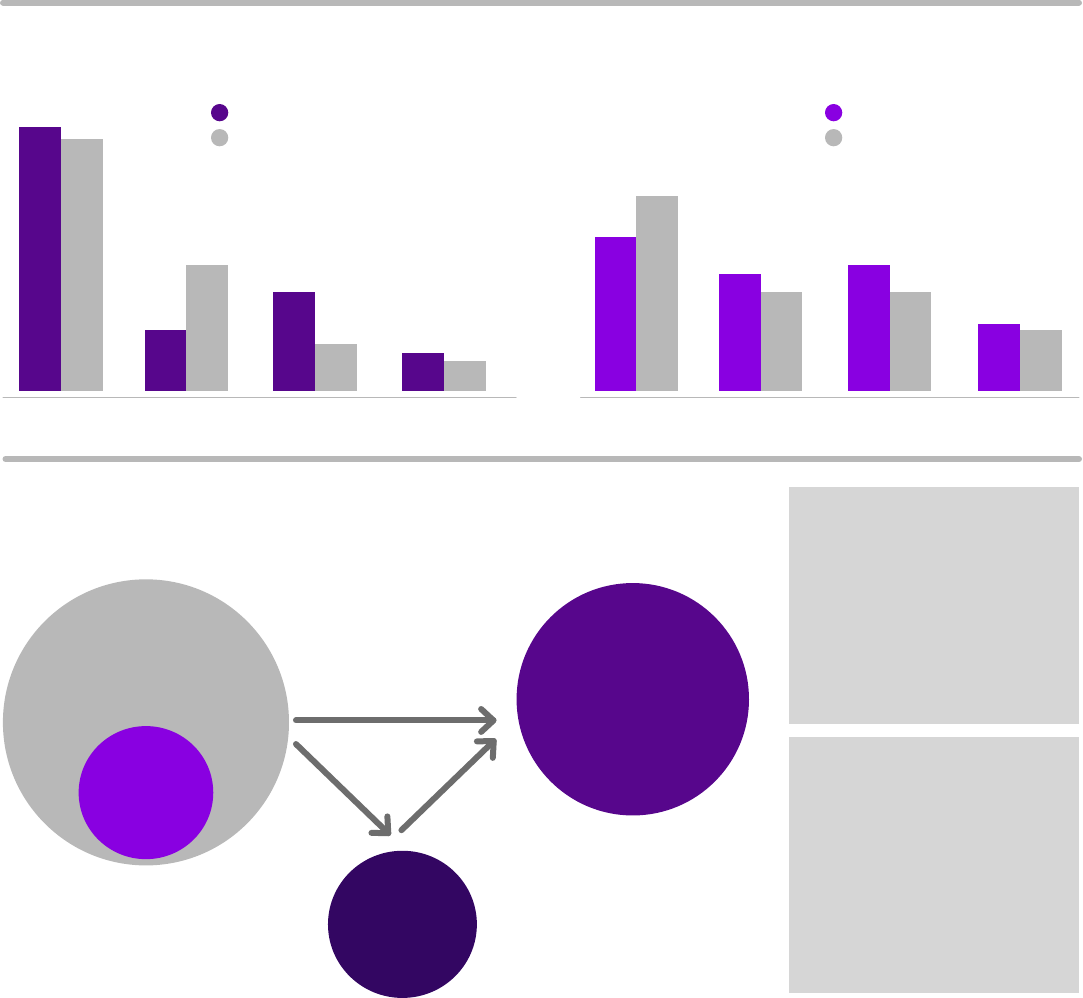

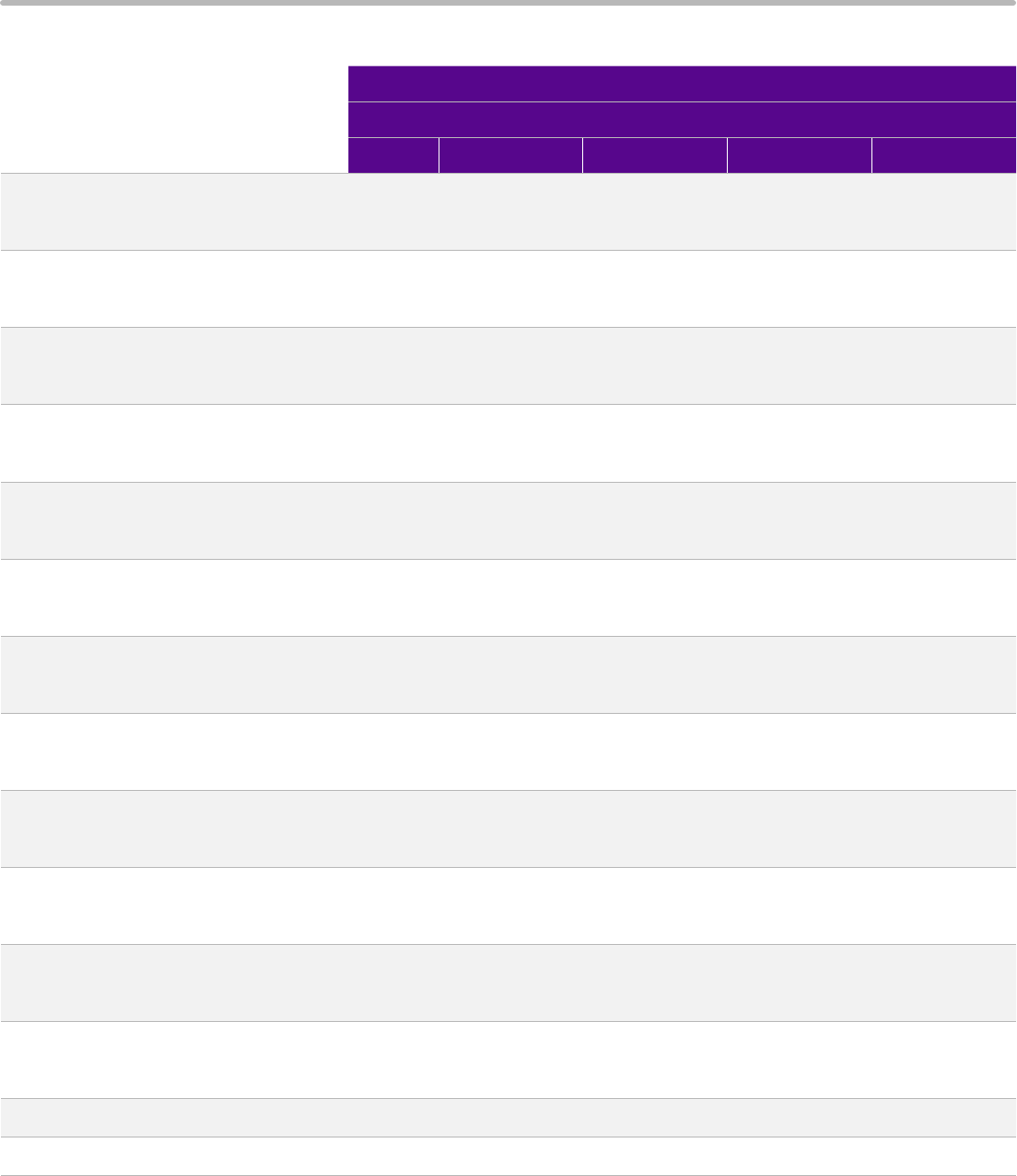

We found a positive relationship between ESG and financial performance for 58% of the “corporate” studies

focused on operational metrics such as ROE, ROA, or stock price with 13% showing neutral impact, 21%

mixed results (the same study finding a positive, neutral or negative results) and only 8% showing a negative

relationship. For investment studies typically focused on risk-adjusted attributes such as alpha or the Sharpe

ratio on a portfolio of stocks, 59% showed similar or better performance relative to conventional investment

approaches while only 14% found negative results. We also found positive results when we reviewed 59

climate change, or low carbon, studies related to financial performance. On the corporate side, 57% arrived

at a positive conclusion, 29% a neutral impact, 9% mixed and, 6% negative. Looking at investor studies, 65%

showed positive or neutral performance compared to conventional investments with only 13% indicating

negative findings. A detailed breakdown can be found in Figure 1.

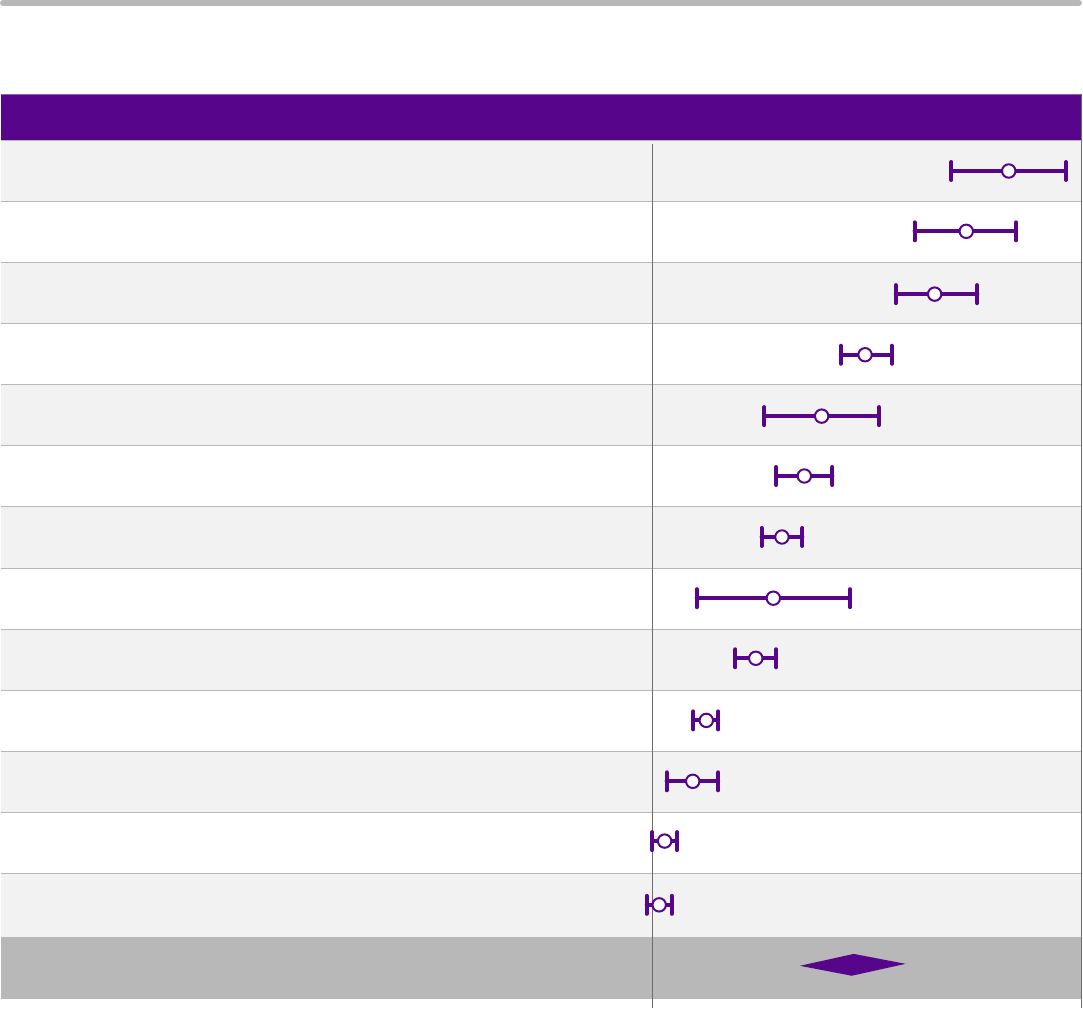

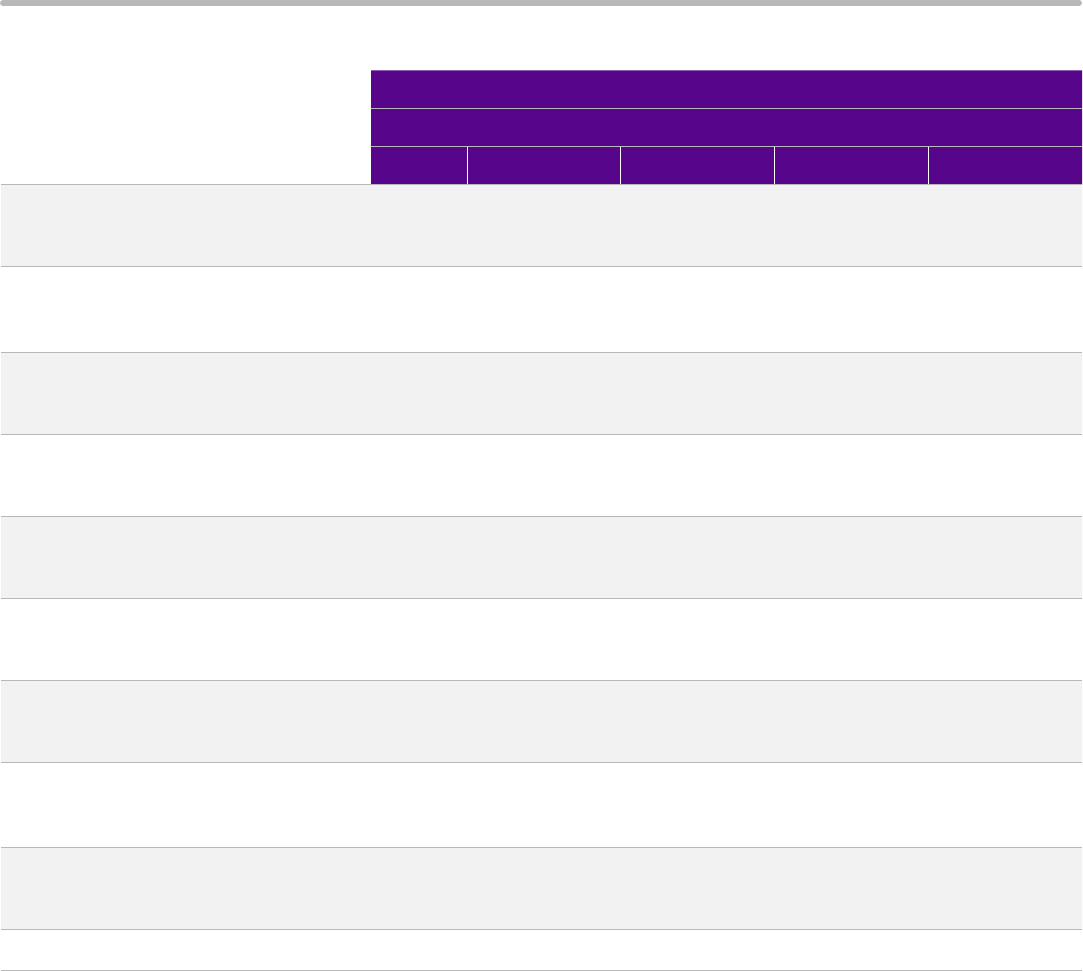

These findings were supported by an additional meta-meta-analysis (a study of existing meta-studies) we

undertook. We found 13 corporate meta-analysis studies published (covering 1,272 unique studies) with a

quantitative approach and 2 investor meta-analysis studies (covering 107 unique studies) published since

2015. The former found consistent positive correlations between ESG and corporate financial performance;

the latter found that ESG investing returns were generally indistinguishable from conventional investing

returns. (Figure 2). We concluded that these two findings are robust across time and space.

Executive Summary

3 ESG and Financial Performance

Research over the last five years appears to be producing more

conclusive results, but it is worth acknowledging the challenges

with inconsistent terminology, insucient emphasis on “material”

ESG issues, ESG data shortcomings, and confusion regarding

dierent ESG investing strategies.

• Research covering ESG and financial performance often suers

from inconsistent terminology and nomenclature. Meuer et al.

(2019) found 33 definitions of corporate sustainability in usage.

For corporations, embedded sustainability (ESG is part of the

business strategy) may have dierent performance implications

than traditional Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) eorts

that emphasize community relations and philanthropy, yet

there has been insucient review of those dierences, creating

noise in the findings (Douglas et al., 2017). We see some of

that confusion in a study by Manchiraju and Rajgopal (2017)

which assessed the (poor) financial performance of companies

required to spend 2% of their profits on CSR by the Indian

government. In this case, CSR was philanthropy and community

relations, not sustainability related to the material ESG issues

that could enhance long-term performance.

• Research often fails to distinguish between material and

immaterial ESG issues as well as ESG leaders versus improvers. For

example, Khan et al. (2016) demonstrate the alpha potential when

incorporating “material” ESG issues, with the stock performance

of companies focused on material issues outperforming those

that focuses on immaterial ESG issues or no ESG issues at all.

Rockefeller Asset Management’s research shows similar results:

one study emphasizes that ESG integration will increasingly be

demarcated between “Leaders” and “Improvers” and finds long-

term alpha enhancing potential when focusing on material ESG

issue improvement (Clark & Lalit, 2020).

• The results are also complicated by the lack of standardization

with ESG data. Studies use dierent scores for dierent

companies by dierent data providers. Eccles et al. (2017), for

example, reviewed a global survey of institutional investors and

concluded that “the biggest barrier is the lack of high quality

data about the performance of companies on their material

ESG factors.” Plenty of technical evidence also points to the

shortcomings of accounting metrics and ESG data (Berg et

al., 2019). We found that at least 40% of studies relied on an

overall, third-party ESG score.

• ESG integration, ESG momentum, decarbonizing, socially

responsible investing (SRI), negative screening, and impact

investing are just a few of the varied approaches referenced

in the research. They are often merged together, even though

each has dierent risk-reward implications. A common research

approach is to query Bloomberg for funds labeled ESG – those

funds are self-designated, and may lack a robust ESG investing

framework. Studies can also confuse the outcome by failing to

distinguish between performance of a strategy seeking market

rate or excess returns versus a strategy prioritizing positive

environmental and social impact while accepting concessionary

We drew six conclusions about

the relationship between ESG

and financial performance after

examining the 1000 plus

individual studies.

Improved financial

performance due to ESG

becomes more marked over

longer time horizons.

ESG integration, broadly

speaking as an investment

strategy, seems to perform

better than negative

screening approaches. A

recently released Rockefeller

Asset Management study

finds that ESG integration

will increasingly be

demarcated between

“Leaders” and “Improvers”

with the latter showing

uncorrelated alpha-

enhancing potential over

the long-term (Clark &

Lalit, 2020).

ESG investing appears

to provide downside

protection, especially during

a social or economic crisis.

Sustainability initiatives

at corporations appear

to drive better financial

performance due to

mediating factors such as

improved risk management

and more innovation.

Studies indicate that

managing for a low carbon

future improves financial

performance.

ESG disclosure on its own

does not drive financial

performance.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

4 ESG and Financial Performance

returns. Hernaus (2019) is an exception: she found that financial performance diered based on the

sustainable investing strategy employed by European fund managers. She writes, “previous studies have

predominantly treated SRI as homogeneous (Schroeder, 2007; Rathner, 2013) and have not distinguished

between particular, dierent SRI strategies available, whose number and diversity (European Sustainable

Investment Forum – Eurosif, 2012; US SIF, 2012; European Fund and Asset Management Association, 2016)

reflect the great heterogeneity of this financial phenomenon (Sandberg et al., 2009).” Investors seem

to be making a distinction; Eurosif found that ESG integration grew at a compound annual growth rate

(CAGR) of 27%, while negative screening fell 3% (Eurosif, 2018).

Some of the earlier short-comings in the corporate research have been addressed in the last five years,

which may be why we have more clear positive findings. However, academic researchers continue to be

challenged by the variability of ESG data and the lack of distinction between dierent investment strategies,

creating an opportunity for investors and researchers who can overcome this challenge. Judging from the

fact that the volume of research produced since 2015 is comparable to all papers published before 2015, this

is clearly an area where we should expect to see increased and improved research in coming years.

Figure 1. Positive and/or neutral results for investing in sustainability dominate. Very few studies found a negative

correlation between ESG and financial performance (based on 245 studies published between 2016 and 2020) .

Corporate (all)

Corporate (climate change)

Mixed

22%

28%

Mixed

9%

21%

Investor (all)

Investor (climate change)

Neutral

29%

13%

Negative

13%

14%

Positive

58%

57%

Figure 2. Conceptual overview of how investing in sustainability/ESG drives financial

performance: We reviewed and categorized relevant academic studies and analyzed

them through correlations, mediating factors, and a specific theme – climate change.

Investor-focused studies

tend to look at a direct

relationship between ESG

and performance based on

benchmarks and a portfolio-

level view of themes such as

materiality or governance

structure. Meta-analytical

eects are Hedges’ g or d.

Corporate-focused studies

may include mediating

factors such as innovation,

operational eciency, or

risk management for a

better understanding of how

sustainability initiatives lead

to CFP. Meta-analytical eects

are partial correlations from

regression models.

Sustainability

strategy

& practice

Corporate financial

performance

(CFP) or market

performance

Climate

change

action

Correlation

Mediation

Neutral

22%

26%

Positive

33%

43%

Negative

6%

8%

5 ESG and Financial Performance

In reviewing over 1,000 studies published between

2015 – 2020, we found a positive relationship

between ESG and financial performance for 58%

of the “corporate” studies focused on operational

metric such as ROE, ROA, or stock price with 13%

showing neutral impact, 21% mixed results (the same

study finding a positive, neutral or negative results)

and only 8% showing a negative relationship. For

investment studies typically focused on risk-adjusted

attributes such as alpha or the Sharpe ratio on a

portfolio of stocks, 33% found positive performance

26% found neutral impacts (in other words,

performed similar to conventional investments), 28%

had mixed results (positive, neutral, or negative,

generally because they examined a variety of

variables and time periods as well as multiple

samples in one study) and 14% found negative

results. In other words, 59% showed similar or better

performance relative to conventional investment

approaches while only 14% found negative results.

We also found positive results when we reviewed

59 climate change, or low carbon, studies related

to financial performance. On the corporate side,

57% arrived at a positive conclusion, 29% a neutral

impact, 9% mixed and, 6% negative. Looking at

investor studies, 65% showed positive or neutral

performance compared to conventional investments

with only 13% indicating negative findings. A detailed

breakdown is found in Figure 1.

These findings were supported by an additional

meta-meta-analysis (a study of existing meta-studies)

we undertook. We found 13 corporate meta-analysis

studies published (covering 1,272 unique studies) with

a quantitative approach and 2 investor meta-analysis

studies (covering 107 unique studies) published since

2015. The former found consistent positive correlations

between ESG and corporate financial performance;

the latter found that ESG investing returns were

generally indistinguishable from conventional investing

returns. (Figure 2). We concluded that these two

findings are robust across time and space.

Many of the studies reviewed described a finding

and tried to explain it through the lens of a social

science derived model of the world. Several social

science theories dominate the research:

• Stakeholder theory (successful companies need

to manage for a wide variety of stakeholders

such as employees, civil society, suppliers and

investors),

• Shared value (companies that create shared value

for all stakeholders do better financially),

• Legitimacy theory (a social contract between the

corporation and society, which, if broken, leads

to consumers reducing demand or governments

imposing regulatory restrictions),

• Resource-based view (emphasizing internal

resources such as employees and intangible assets

for achieving a competitive advantage).

Studies most often invoked stakeholder theory

(N=80), but shared value, legitimacy theory and the

resource-based view appeared in a sizeable share of

studies (16% - 25%).

Notably, those studies that did not include a social

science theory only found a one-in-three positive

association with ESG and financial performance,

whereas the odds were one-in-two on average for

research grounded in social science theories.

This finding points toward the need to better

understand the mechanisms behind the relationship

between ESG and financial performance. Ioannou

and Serafeim (2019) in Corporate Sustainability: A

Strategy? took a closer look at whether sustainability

might be considered a strategic approach (leading

to a competitive advantage) or common practice

(a set of standards within an industry that confer

legitimacy). They find that both options are relevant

and that adoption of sustainability over time is

complex and dynamic.

The Results Indicate an

Encouraging Relationship between

ESG and Financial Performance

6 ESG and Financial Performance

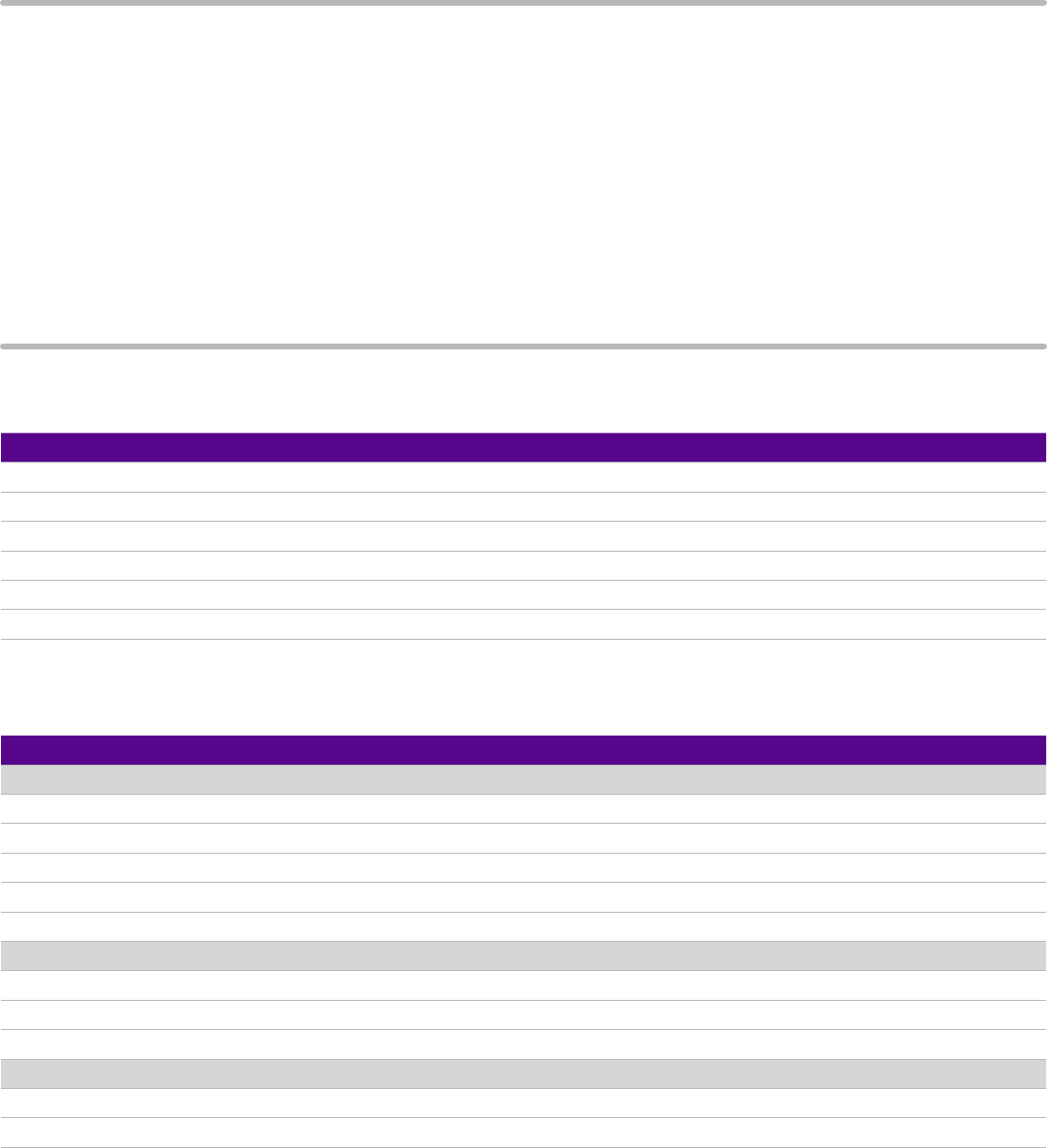

Figure 3. Twelve of thirteen meta-analyses (comprising 1,272 studies) found a positive association between some aspects

of sustainability and financial performance (1976-2018).

Study estimate 95% confidence/credible interval

Lopez-Arceiz et al. 2018 0.199 [0.166, 0.232]

Lu & Taylor 2016 0.174 [0.145, 0.202]

Hou et al. 2016 0.158 [0.134, 0.182]

Busch & Friede 2018 0.119 [0.104, 0.134]

Plewnia & Guenther 2017 0.094 [0.062, 0.126]

Gallardo-Vazquez et al. 2019 0.084 [0.068, 0.100]

Hang et al. 2019 0.072 [0.060, 0.084]

del Mar Miras-Rodgriguez et al. 2015 0.067 [0.023, 0.111]

Wang et al. 2016 0.059 [0.045, 0.072]

Vishwanathan et al. 2019 0.030 [0.022, 0.038]

Hoobler et al. 2018 0.023 [0.007, 0.039]

Jeong & Harrison 2017 0.007 [0.001, 0.013]

Rost & Ehrmann 2017 0.004 [-0.004, 0.012]

Modeled mean estimate 0.089 [0.053, 0.127]

0 0.24

7 ESG and Financial Performance

1. Improved financial performance due to ESG

becomes more marked over a longer time horizon

We found that our proxy for an implied long-term

relationship had a coecient with a positive sign

that is statistically significant. The model suggests

that, everything else being constant, a study with

an implied long-term focus is 76% more likely

to find a positive or neutral result. Hang et al.

(2019) undertook a meta-analysis (N=142) which

found corporate investments in environmental

sustainability had no eect on corporate financial

performance in the short term, but had positive

eects over the longer-term. Some recent papers

were optimistic about how markets value long-

term commitments. Kotsantonis et al. (2019) found

that CEOs communication of “long-term plans”

resulted in an abnormal positive reaction by the

stock market. A cross-sectional study on firms

with strong ESG ratings found returns up to 3.8%

higher per standard deviation of ESG score in the

mid- and long-term (Dorfleitner et al., 2018).

2. ESG Integration as a strategy seems to perform

better than negative screening approaches

and ESG momentum may cause improvers to

outperform leaders

The sample size of studies on specific portfolio

management strategies and asset classes was

small, making it challenging to interpret how they

would translate into decision-making for an asset

manager. The dominant research approach was

to find a sample of sustainable funds or indices

and compare them to a conventional benchmark.

Most of the research focused on equities (N=54,

with 33% finding alpha, 54% finding a neutral or

mixed eect) rather than fixed income (N=11, with

19% finding alpha and 56% finding a neutral or

mixed eect). In addition, most studies focused

on active (N=41, with 29% alpha and 56% neutral

or mixed) vs passive (N=6) investing.

We also looked at the explicit or implicit

investment strategies that underpin the analysis

in the academic studies (they serve as proxy

for “real-world” applicability; for example,

researchers may define a universe of available

ESG funds or use an ESG score in a regression

model). We found ESG integration seemed

to perform better than negative screening

and divesting, with 33% of the (N=17) studies

finding alpha and 53% finding neutral or mixed

results. The subgroup of papers analyzing

pooled investment strategies (combining

everything with some type of ESG label) was

least convincing in terms of showing a positive

association (65% less likely). We speculate it

might be because too many dierent strategies

were combined together. For example, this

group contains socially responsible investing

(SRI) and ethical funds that may not have an

ambition to match or outperform a conventional

benchmark. Ielasi et al. (2018) compared

dierent sustainable investing strategies with

each other and indeed found performance

dierences between passive and active and

ethical versus ESG integration strategies.

Very few studies emphasized material ESG

issues and demarcated between ESG Leaders,

or best-in-class firms, and ESG Improvers,

or firms showing the greatest improvement

in their ESG footprint. One seminal paper

titled Corporate Sustainability: First Evidence

on Materiality published in 2016 by Kahn,

Serafeim and Yoon from Harvard Business

School showed the outperforming potential of

mapping material ESG issues and emphasizing

momentum, or ESG improvement (Khan et al.,

2016). Rockefeller Asset Management’s research

further supports these results. In their paper,

ESG Improvers: An Alpha Enhancing Factor,

they use materiality mapping to dierentiate

between ESG Leaders and ESG Improvers, and

demonstrate the alpha potential of the latter in

a study covering US equities from 2010 – 2020.

Six Key Takeaways

8 ESG and Financial Performance

The key takeaways from the research include:

• A back-tested, hypothetical portfolio of top-

quintile ESG Improvers outperformed bottom-

quintile ESG “Decliners” by 3.8% annualized in

an analysis covering US all cap equities from

2010 – 2020. The signal is monotonic, in that

outperformance grew with each quintile.

• An optimized hypothetical ESG Improvers

portfolio, which seeks to isolate pure ESG

improvement while controlling for sector and

factor biases, generated 0.5% annualized

excess returns from 2010 – 2020 with 1.3%

tracking error relative to the Bloomberg US

3000 Index.

• The ESG Improvers factor enhanced returns

when integrated with traditional factors

over the back-test period. A hypothetical

multi-factor ESG Improvers + Quality + Low

Volatility portfolio outperformed a two-

factor Quality and Low Volatility portfolio by

0.45% annualized. Over the same time period,

an ESG Improvers + Value + Momentum

Portfolio outperformed a two-factor Value and

Momentum portfolio by 1.1% annualized.

3. ESG investing appears to provide downside

protection, especially during social or

economic crisis

ESG investing appears to provide asymmetric

benefits. As discussed below, investor studies

in particular seem to demonstrate a strong

correlation between lower risk related to

sustainability and better financial performance.

Recent events have provided unique datasets

for researchers. During the financial crisis

(2007-2009) Fernández et al. (2019) found

that German green mutual funds delivered

risk-adjusted returns slightly better than their

peers (during non-crisis they were equal to

conventional funds, but better than SRI funds).

Similarly, the FTSE4Good, a set of ESG stock

market indices, performed better and recovered

its value quicker after the 2008 financial crash

(Wu et al., 2017). These findings seem to hold in

general for economic downturns as high rated

ESG mutual funds outperformed low rated funds

based on the Sharpe ratio (Chatterjee, 2018; Das

et al., 2018). Finally, in the first quarter of 2020

COVID downturn, 24 of 26 ESG index funds

outperformed their conventional counterparts,

which they credited ESG leading to more

resiliency and at the end of the third quarter, 45%

of ESG-focused funds outperformed their index

(Morningstar, 2020). While virtually all studies,

by academics and practitioners alike found this

correlation, one outlier, based on ESG scores, did

not find such a correlation (Demers et al., 2020)

4. Sustainability initiatives at corporations appear

to drive financial performance due to factors

such as improved risk management and more

innovation

Sustainability strategies implemented at the

corporate level can drive better financial

performance through mediating factors—i.e.

the sustainability drivers of better financial

performance such as more innovation, higher

operational eciency, better risk management,

and others, as defined in the Return on

Sustainability Investment (ROSI) framework (Atz

et al., 2019). We reviewed the studies through the

lens of these mediating factors and found that

stakeholder relations, risk, operational eciency,

and innovation were the most common in the

literature. For example, Vishwanathan et al.

(2019) reviewed 344 studies and identified four

mediating factors – enhancing firm reputation,

increasing stakeholder reciprocation, mitigating

firm risk, and strengthening innovation capacity –

which drove financial performance.

Our regression analysis reviewed 17 studies that

included some aspect of innovation in their

analysis, and all had positive findings regarding

related financial performance. However, some

of these studies did not exclusively focus on

innovation and so the individual eect is hard

to separate out. In addition, the small sample

size reduces the level of confidence; thus we see

this as an exciting area for further research. For

operational eciency, more than half of the 22

studies (59%) found a positive correlation between

operational eciency and financial performance;

only three of the 22 had a negative finding.

Regarding risk, we found that investor studies

that did not include risk as a mediating factor

were only 27% likely to find a positive correlation

with financial performance, while 48% of

those studies that did include risk were likely

to find a positive result. And 52% of the 40

studies across all studies looking at risk found

a positive correlation. For example, portfolios

with lower ESG risks can maintain risk-adjusted

performance (Hübel & Scholz, 2020). Gloßner

(2018) concluded that controversial firms with

9 ESG and Financial Performance

a known history of ESG incidents exhibit “a

four-factor alpha of −3.5% per year, even when

controlling for other risk factors, industries, or

firm characteristics.” In addition, with regards to

climate-change related risk, 51% of the studies

found a positive correlation between better

financial performance and managing for physical

and transition risk related to climate change.

Overall, no single mediating factor resulted in a

statistically significant eect in our model; partly

because the underlying samples are small and

partly because the eects are hard to isolate

in studies that mostly look very broadly at the

relationship between sustainability and financial

performance. More research is needed in this area.

5. Studies indicate that managing for a low carbon

future improves financial performance

Research on mitigating climate change

through decarbonization strategies is fairly

recent, but finds strong evidence for better

financial performance for both corporates and

investors. Unfortunately, none of the three elite

finance journals (Journal of Finance, Journal of

Financial Economics, and Review of Financial

Studies) published a single article related to

climate change over their analysis period (Diaz-

Rainey et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2019), which

we corroborated. However, 59 studies on the

relationship between low carbon strategies and

financial performance were published elsewhere

in the last five years, and the majority uncovered

a positive result. Mitigating risk was the focus

on many of the studies, as discussed earlier. For

example, Cheema-Fox et al. (2019) examined

the construction of decarbonization factors and

found that dierent decarbonization strategies

generate dierent risk-adjusted returns. In

particular, they found strategies that lowered

carbon emissions more aggressively performed

better. In, Park, and Monk (2019) assessed 736

US public firms from 2005 to 2015, and found

that a strategy of going long on carbon ecient

firms and shorting carbon inecient firms could

earn an annual abnormal return of 3.5%-5.4%.

Their research indicates that investing in carbon-

ecient firms can be profitable even without

government incentives.

Few studies focused on the investment

implications of investing in companies producing

climate mitigation or adaption solutions,

which diers from decarbonizing portfolios.

This is a promising area of research. It seems

likely that climate change will transform

economies and markets through changing

regulations, changing consumption patterns,

especially from next generation consumers,

and technological advancements. As a proof

point, FTSE’s Opportunities All Share Index - an

index that includes companies with involvement

in Renewable & Alternative Energy, Energy

Eciency, Water Infrastructure and Technology,

Waste Management & Technologies, Pollution

Control, Environmental Support Services, and

Food, Agriculture & Forestry – outperformed its

traditional counterpart, FTSE Global All Cap Index

by 4.9% annualized over the five-year period from

October 2015 – October 2020.

6. ESG disclosure on its own does not drive

financial performance

Just 26% of studies that focused on disclosure

alone found a positive correlation with financial

performance compared to 53% for performance-

based ESG measures (e.g. assessing a firm’s

performance on issues such as greenhouse

gas emission reductions). This result holds in

a regression analysis that controls for several

factors simultaneously. While what gets measured

does matter, measuring ESG metrics without an

accompanying strategy seems ineective. For

example, signatories to the UN Principles for

Responsible Investment agreed to implement

ESG policies, but the focus is on disclosure versus

performance and Kim and Yoon (2020) found

that the signatories on average improved neither

the ESG nor the financial performance of their

portfolios. In more general terms, Fatemi et al.

(2018) specifically distinguished between ESG

disclosures and performance. While high (low)

ESG performance increased (decreased) firm

value, they also found that ESG disclosures on

their own had a negative valuation eect.

10 ESG and Financial Performance

Our analysis of more than 1,000 research papers

exploring the linkage between ESG and financial

performance since 2015 points to a growing

consensus that good corporate management of

ESG issues typically results in improved operational

metrics such as ROE, ROA, or stock price. For

investors seeking to construct portfolios that

generate alpha, some ESG strategies seem to

generate market rate or excess returns when

compared to conventional investment strategies,

especially for long-term investors, and provide

downside protection during economic or social crisis.

Notably, very few studies found definitive negative

correlations between ESG and financial performance.

Unfortunately, studies to help us understand why

these correlations exist were lacking. There were

very limited studies on mediating factors such as

innovation and operational eciencies that might

drive better corporate performance. And most

investment studies did not clearly demarcate the

diering risk-reward outcomes of varying ESG

integration approaches, nor did they analyze

the dierent performance implications of ESG

leaders (best-in-class firms) versus ESG improvers

(firms showing the greatest improvement in their

ESG footprint). Finally, thematic studies are also

relatively limited although climate change studies

show promise; research shows a strong relationship

between decarbonization strategies and improved

performance.

Studies need to better distinguish between dierent

types of investment strategies and asset classes in

order to analyze financial performance. Thematic

studies on material issues such as climate change

provide an intriguing approach as focusing on one

issue may lead to more conclusive results. We also

recommend that future meta-analyses distinguish

between corporate and investor studies as we have

done. Finally, an area that has been woefully under

researched is the causal factors for improved financial

performance by corporates with robust sustainability

strategies – we recommend more research into

sustainability-driven innovation, employee relations,

supplier loyalty, customer demand, risk mitigation,

operational eciency, and so on.

We look forward to reviewing the field of the

research in 2025!

Conclusion

11 ESG and Financial Performance

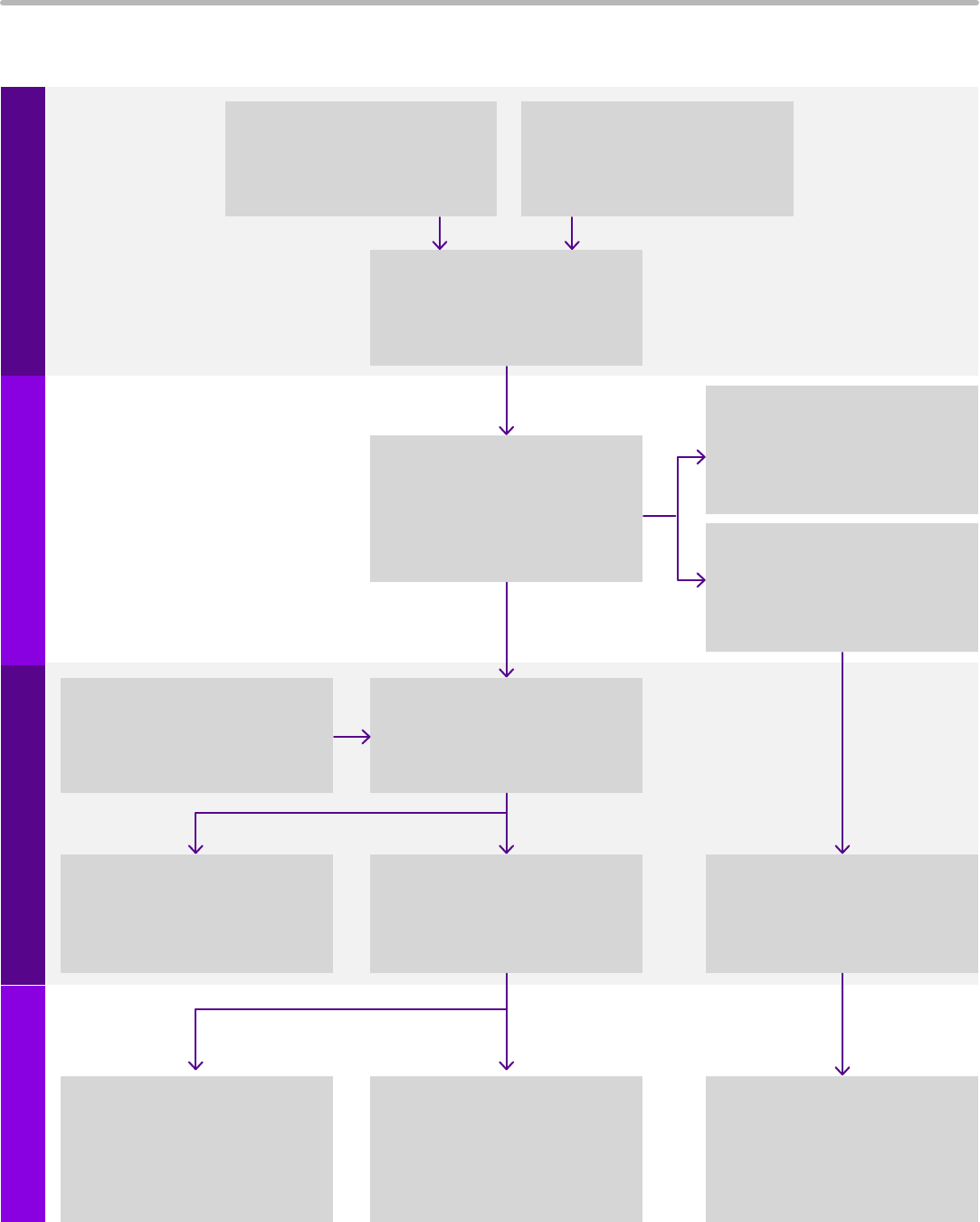

To understand dierences in studies in a systematic manner, we disaggregated the research into three types:

1. Studies that analyzed how corporations with sustainability initiatives performed financially.

These studies typically used a panel of public companies, a commercially available ESG score or an

environmental/social performance metric, and may include mediating factors such as innovation,

operational eciency, or risk management for a better understanding of how sustainability initiatives

lead to corporate financial performance (Vishwanathan et al., 2019). Here, we relied on our codebook

(Supplement 1) and investigated how innovation, operational eciency, risk management and other

mediating factors were present in the academic literature.

2. Studies that analyzed how ESG funds, portfolios, or indices performed financially. Most investment-oriented

research on ESG and financial performance was at a portfolio level of an asset class using some metric of

risk-adjusted return, for example, comparing alpha in conventional and sustainable mutual funds. More recent

studies also looked at issues such as materiality (Khan et al., 2016) or investment management strategies such

as negative screening. Here, we analyzed the investor-focused research, which ESG investment strategies

were considered, and how the investor research compared to the corporate research.

3. Studies that analyzed a specific theme such as climate change, which can be relevant for managers and

investors. A third type of study focuses on a specific ESG theme. We chose climate change because it is a

new and growing area of financial risk for managers and investors that also presents opportunities. Here, we

gathered studies and industry reports and examined the role of climate change for asset managers.

We searched ProQuest, Web of Science (WoS), Google Scholar, Social Science Research Network (SSRN),

National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), and other journal databases for two sets of keywords: related to

sustainability/ESG and related to financial performance/CFP. Examples of the search queries are shown in Table

A1 in the Appendix. We restricted the search for the period of January 2015 to February 2020 to find relevant

studies that were published in English. We used various validation strategies to achieve a comprehensive sample.

To develop the final sample (Figure 2), we screened (level 1) academic papers that examined the causal

relationship between sustainability and financial performance. The rapid title screening identified relevant

studies based on three quick heuristics that screened for results that we hoped generalize the most:

1. Is financial performance a dependent variable (outcome)?

2. Does a “sustainability variable” lead to a quantitative result?

3. Is there more than one company or fund being investigated?

In level 2 screening, we attempted to find the relevant section for the codebook (see Supplement 1) in the

full text such as definition of variables or a results table. The full set of eligible articles (1,141) was further

reduced, so that we could focus on coding studies for the quantitative synthesis. All quantitative meta-

analyses (n = 15) published in the reference frame were coded to achieve a dataset suitable for a second-

order meta-analysis (see Supplement 2 for details and data).

The median start and end date for an individual study’s data sample was 2007 to 2015. Many studies relied on

long time series with 27% having a mid-point year that was before the financial crisis of 2008. Nineteen percent

of studies used a sector-specific dataset. Geographically most studies focused on the USA (34%) and Europe

(24%) with a sizable share of global (29%) datasets. Over 30% of studies specified a specific country. For the

outcome variables we found that 18% analyzed ESG disclosures only and not ESG performance (and of those

40% used a third-party ESG score such as MSCI KLD). Market-based measures of financial performance (in 76%

of studies) were vastly more popular than accounting-based measures (27%) with some overlap.

Appendix:

Methodology

12 ESG and Financial Performance

The full study and supplement 1 and 2 are available on SSRN:

https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3708495

The NYU Stern Center for Sustainable Business (CSB) envisions a better world through better business.

CSB was founded on the principle that sustainable business is good business, and is proving the value of

sustainability for business management and performance at a time when people and the planet need it

most. Through education, research, and engagement, CSB prepares individuals and organizations with the

knowledge, skills, and tools needed to embed social and environmental sustainability into core business

strategy. In doing so, businesses reduce risk; create competitive advantage; develop innovative services,

products, and processes; while improving financial performance and creating value for society. For more

information, visit CSB’s website: https://www.stern.nyu.edu/sustainability

Appendix:

Summary Charts and Exhibits

Table 1. Cross-tabulations for the mediating factor risk management and overall study finding. Note how investor studies

had fewer positive results (27% vs 48%) when the study did not consider risk.

Indicator variables Count Positive Neutral/mixed Negative

Mediating factor risk in corporate studies 16 57% 34% 8%

No mediating factor risk in corporate studies 143 69% 31% 0%

Mediating factor risk in investor studies 23 48% 39% 13%

No mediating factor risk in investor studies 63 27% 59% 14%

Mediating factor risk in thematic studies 13 69% 23% 8%

No mediating factor risk in thematic studies 46 54% 35% 11%

Notes. See Supplement 1: Codebook for all definitions.

Table 2. Selected codes for all studies across overall finding. Interpret rows with low counts with caution.

Indicator variables Count Positive Neutral/mixed Negative

Study design

Disclosure only 50 26% 60% 14%

Performance only 159 53% 39% 8%

Accounting-based measure 67 46% 42% 12%

Market-based measure 186 46% 44% 11%

Aggregate ESG score 48 52% 40% 8%

Casualty proxies

Implied long-term relationship 94 50% 40% 10%

Lagged dependent variable 51 51% 35% 14%

Fixed eects / matching methods / instrumental variables 66 41% 53% 6%

Mediating factors

Risk 40 52% 40% 8%

Operational eciency 22 59% 27% 14%

Innovation 17 76% 24% 0%

13 ESG and Financial Performance

Indicator variables Count Positive Neutral/mixed Negative

Social science theories

Stakeholder theory 80 57% 34% 9%

Legitimacy theory 40 45% 40% 15%

Porter’s hypothesis 40 57% 28% 15%

Resource-based view 64 55% 36% 9%

None 74 32% 57% 11%

Notes. See Supplement 1: Codebook for all definitions.

Table 3. Selected codes for studies of the investor type across overall finding. Interpret rows with low counts with caution.

Indicator variables Count Positive Neutral/mixed Negative

Asset class

Equities 54 33% 54% 13%

Fixed income 11 19% 56% 25%

Management style

Active 41 29% 56% 15%

Passive 6 50% 50% 0%

Portfolio management strategy

Negative screening & divesting 16 19% 69% 12%

Pooled strategies created by researchers 30 10% 73% 17%

ESG integration created by researchers 17 33% 53% 14%

Notes. See Supplement 1: Codebook for further details. Portfolio management strategy: Investors describe practical portfolio management

strategies in many ways, sometimes inconsistent. We broadly follow Matos (2020): “ESG and Responsible Institutional Investing Around the

World: A Critical Review from the CFA Institute Research Foundation.” Existing literature explores several ESG investing strategies in portfolio

management. Oftentimes the strategies are used interchangeably without clear distinctions. Negative screening & divesting is an investing

strategy where companies that do not comply with pre-established ESG principles are excluded from the portfolio. If the paper focuses on the

so-called “sin” industries alone, investing (or not) in the tobacco industry or staying away from oil and gas companies, it is coded as negative

screening, also. For an example see Richey (2016). Pooled strategies as created by researchers: Instead of excluding companies, investors

analyze and select firms and assets that exemplify sustainable business practices. If a paper compares ESG investing versus conventional

investing, such as comparing ESG mutual funds vs. conventional mutual funds, or SRI mutual funds versus conventional mutual funds, or ESG

index vs a benchmark conventional index, the strategy is coded as pooled strategies. For an example see Pereira et al. (2019). ESG integration

as created by researchers incorporates ESG analysis into fundamental research and portfolio construction beyond screening or pooled

strategies. We allowed for two subcodes in this category: ‘best-in-class’ and ‘improvers’. 1) If the paper specifically discusses “best-in-class” or

“improver”, then the paper is coded accordingly. The strategy is coded as best-in-class or improver when the strategy is the subject of study

in the paper, or the paper employs the strategy in portfolio construction. In this case, we code the paper accordingly. 2) If the paper does

not distinguish best-in-class and improver but rather using “ESG integration” as a generic strategy, then both strategies are selected. 3) If the

paper discusses ESG momentum strategy or the impact of ESG on momentum portfolios without distinguishing between best-in-class or

improvers, the strategy is coded as both (Kaiser & Welters, 2019; Yen et al., 2019).

Table 4. Selected codes for studies of the climate change issue type across overall finding.

Interpret rows with low counts with caution.

Indicator variables Count Positive Neutral/mixed Negative

Risk management

Physical risk 41 51% 39% 10%

Transitional risk 35 51% 40% 9%

Dynamic materiality / scenario 9 67% 11% 22%

Notes. See Supplement 1: Codebook for all definitions.

14 ESG and Financial Performance

Table 5. Ordered logit regression model for all studies

Dependent variable

Overall finding (negative, neutral/mixed, positive)

1 2 3 4 5

Investor perspective (vs corporate)

-0.976*** -1.103*** -0.882*** -0.992*** -1.129***

(0.263) (0.316) (0.346) (0.286) (0.381)

Climate change issue (vs not)

0.21 0.252 -0.006 0.153 0.09

(0.297) (0.31) (0.384) (0.304) (0.395)

ESG disclosure (vs performance)

-0.767** -0.751**

(0.347) (0.37)

Accounting-based (vs market)

-0.856*** -0.842**

(0.322) (0.331)

ESG score (vs E/S/G/other)

0.36 0.451

(0.36) (0.381)

Implied long-term relationship

(vs short term)

0.381 0.568

(0.315) (0.327)

Lagged dependent variable

(vs concurrent)

-0.226 -0.54

(0.389) (0.412)

Fixed eects / matching

methods / instrumental variables

-0.252 -0.262

(0.342) (0.353)

No social science theory

-0.371 -0.214

(0.359) (0.388)

Mediating factor: Risk

0.711* 0.536

(0.394) (0.413)

Mediating factor: Operational eciency

-0.046 0.148

(0.5) (0.539)

Mediating factor: Innovation

1.132* 1.212*

(0.678) (0.689)

Region controls? No Yes Yes Yes Yes

Observations 241 239 241 241 239

Notes. This table shows the result of an ordered logit regression model for all studies with five model specifications. The largest

statistically significant coecient appeared from the investor indicator suggesting that the type of research is one of the main

explanatory variables for positive or negative results. Study design factors were important but proxies for causality or specific mediating

factors were not. The indicator variables for the three mediating factors are proxies and are based on few studies, and they should hence

be interpreted with caution. See Supplement 1: Codebook for the definitions of codes and variables. Standard errors in parentheses;

*p<0.1; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01.

15 ESG and Financial Performance

Table 6. Ordered logit regression model for investor-focused studies

Dependent variable

Overall finding (negative, neutral/mixed, positive)

1 2 3 4 5

Climate change issue (vs not)

0.534 0.356 0.289 0.591 0.206

(0.478) (0.546) (0.508) (0.502) (0.588)

ESG disclosure (vs performance)

-1.334** -1.120*

(0.568) (0.622)

Accounting-based (vs market)

0.144 0.154

(0.923) (0.965)

ESG score (vs E/S/G/other)

-0.082 -0.231

(0.594) (0.623)

Negative screening or divesting

-0.004 -0.028

(0.575) (0.597)

Pooled strategies

-1.146** -1.041

(0.523) (0.559)

ESG integration

0.865* 0.450

(0.520) (0.557)

Active management

0.075 0.451

(0.437) (0.484)

Equities

0.313 -0.083

(0.443) (0.486)

Observations 86 86 86 86 86

Notes. This table shows the result of an ordered logit regression model for investor-focused studies with five model specifications. The

smaller sample size suppressed the power of the statistical tests, but some coecients were comparable in magnitude to the models in

Table 5. Coecients for pooled strategies as defined by researchers were largest among portfolio management strategies suggesting

that papers that relied on that ESG portfolio management selection were more likely to find negative or neutral results. The dierence

between the pooled strategies and ESG integration was statistically significant. See Supplement 1: Codebook for the definitions of codes

and variables. Standard errors in parentheses; *p<0.1; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01.

16 ESG and Financial Performance

Level 1

Screening

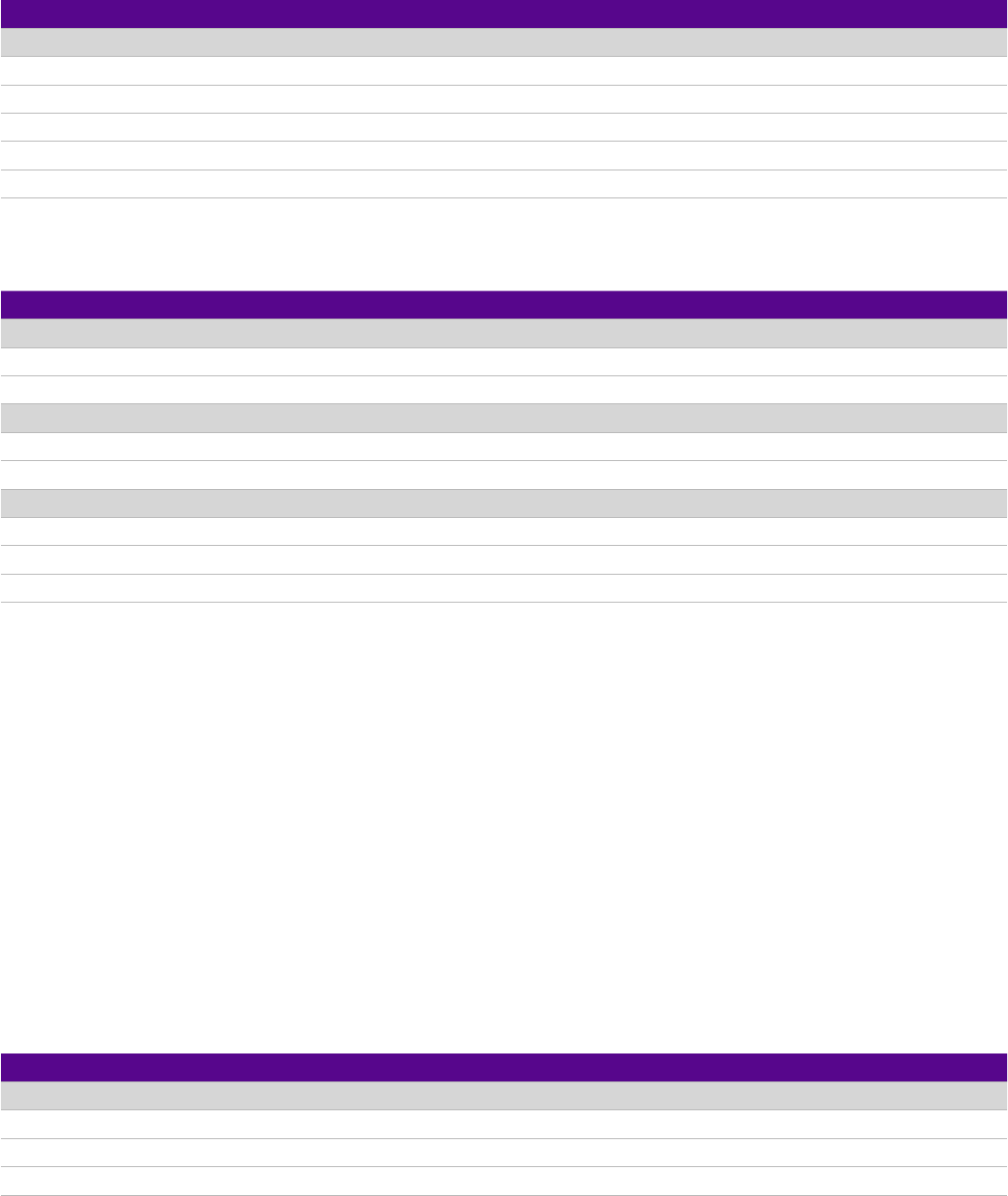

Figure 4. Study selection based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)

guidelines. M = corporate/manager type; I = investor/asset manager type; CC = climate change; n = count

Identification

Level 2

Screening

Inclusion

Records identified through

database searching

(M = 2416; I = 181; CC = 183)

Records screened

(M = 2,359; I = 173; CC = 182)

Full-text articles screenend

and eligible

(n =1,141)

Studies that are prioritized

and eligible

(M = 579; I = 103; CC = 105)

Studies included in

quantitative synthesis

(M = 159; I = 86; CC = 59)

Studies included in qualitative

synthesis (meta-analyses)

(n = 27)

Studies included in quantitative

synthesis (meta-analyses)

(n = 15)

Additional records identified

through other sources

(n = 46)

Full-text articles de-prioritized

(year = 2015, 2016)

(n = 354)

Balance filter for M only

(impact factor; stratification)

(n = 420)

Records excluded

(n = 1,465)

Records labeled as

background papers

(n = 108)

Additional records identified

through validation eorts

(M = 12; I = 13; CC = 41)

Records after duplicates

removed

(n = 2,714)

17 ESG and Financial Performance

Atz, U., Van Holt, T., Douglas, E., & Whelan, T. (2019).

The Return on Sustainability Investment (ROSI):

Monetizing Financial Benefits of Sustainability

Actions in Companies. Review of Business, 39(2).

Berg, F., Kölbel, J., & Rigobon, R. (2019). Aggregate

Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings.

SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/

ssrn.3438533

Chatterjee, S. (2018). Fund Characteristics and

Performances of Socially Responsible Mutual Funds:

Do ESG Ratings Play a Role? ArXiv:1806.09906

[q-Fin]. http://arxiv.org/abs/1806.09906

Cheema-Fox, A., LaPerla, B. R., Serafeim, G.,

Turkington, D., & Wang, H. (2019). Decarbonization

Factors. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10/

ggkrb6

Cheema-Fox, A., LaPerla, B. R., Serafeim, G., &

Wang, H. (Stacie). (2020). Corporate Resilience and

Response During COVID-19 (SSRN Scholarly Paper

ID 3578167). Social Science Research Network.

https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3578167

Clark, C., & Lalit, H. (2020). ESG Improvers: An Alpha

Enhancing Factor. Rockefeller Capital Management.

https://rcm.rockco.com/insights_item/esg-

improvers-an-alpha-enhancing-factor/

Das, N., Chatterje, S., Ruf, B., & Sunder, A. (2018).

ESG Ratings and the Performance of Socially

Responsible Mutual Funds: A Panel Study. Journal of

Finance Issues, 17(1), 49–57.

Demers, E., Hendrikse, J., Joos, P., & Lev, B. (2020).

ESG Didn’t Immunize Stocks Against the COVID-19

Market Crash (SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3675920).

Social Science Research Network. https://doi.

org/10.2139/ssrn.3675920

Diaz-Rainey, I., Robertson, B., & Wilson, C. (2017).

Stranded research? Leading finance journals are

silent on climate change. Climatic Change, 143(1–2),

243–260. https://doi.org/10/gbmz8g

Dorfleitner, G., Utz, S., & Wimmer, M. (2018). Patience

pays o – corporate social responsibility and long-

term stock returns. Journal of Sustainable Finance &

Investment, 8(2), 132–157. https://doi.org/10/ggk2kd

Douglas, E., Van Holt, T., & Whelan, T. (2017).

Responsible Investing: Guide to ESG Data Providers

and Relevant Trends. The Journal of Environmental

Investing, 8(1), 92–114.

Eccles, R. G., Kastrapeli, M. D., & Potter, S. J. (2017).

How to Integrate ESG into Investment Decision-

Making: Results of a Global Survey of Institutional

Investors. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance,

29(4), 125–133. https://doi.org/10.1111/jacf.12267

Eurosif. (2018). European SRI 2018 Study. http://

www.eurosif.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/

European-SRI-2018-Study.pdf

Fatemi, A., Glaum, M., & Kaiser, S. (2018). ESG

Performance and Firm Value: The Moderating Role

of Disclosure. Global Finance Journal, 38, 45–64.

EconLit. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfj.2017.03.001

Fernández, M. S., Abu-Alkheil, A., & Khartabiel, G.

M. (2019). Do German Green Mutual Funds Perform

Better Than Their Peers? Business and Economics

Research Journal, 10(2), 297–312. https://doi.org/10/

ggkrbb

Glossner, S. (2018). The Price of Ignoring ESG

Risks (SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3004689). Social

Science Research Network. https://papers.ssrn.com/

abstract=3004689

Hang, M., Geyer-Klingeberg, J., & Rathgeber, A.

W. (2019). It is merely a matter of time: A meta-

analysis of the causality between environmental

performance and financial performance. Business

Strategy and the Environment, 28(2), 257–273.

Hernaus, A. I. (2019). Exploring the strategic variety

of socially responsible investment—Financial

performance insights about SRI strategy portfolios.

Sustainability Accounting Management and Policy

Journal, 10(3), 545–569. https://doi.org/10.1108/

SAMPJ-07-2018-0182

Hübel, B., & Scholz, H. (2020). Integrating

sustainability risks in asset management: The role

of ESG exposures and ESG ratings. Journal of Asset

Management, 21(1), 52–69.

Ielasi, F., Rossolini, M., & Limberti, S. (2018).

Sustainability-themed mutual funds: An empirical

examination of risk and performance. Journal of Risk

Finance, 19(3), 247–261. https://doi.org/10.1108/JRF-

12-2016-0159

In, S. Y., Park, K. Y., & Monk, A. H. B. (2019). Is “Being

Green” Rewarded in the Market?: An Empirical

Investigation of Decarbonization and Stock Returns

(SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3020304). Social Science

Research Network. https://papers.ssrn.com/

abstract=3020304

References

18 ESG and Financial Performance

Ioannou, I., & Serafeim, G. (2019). Corporate

Sustainability: A Strategy? In SSRN Electronic

Journal. Harvard Business School Accounting

& Management Unit. https://doi.org/10.2139/

ssrn.3312191

Khan, M., Serafeim, G., & Yoon, A. (2016). Corporate

Sustainability: First Evidence on Materiality. The

Accounting Review, 91(6), 1697–1724. https://doi.

org/10.2308/accr-51383

Kim, S., & Yoon, A. (2020). Analyzing Active

Managers’ Commitment to ESG: Evidence

from United Nations Principles for Responsible

Investment. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.

org/10.2139/ssrn.3555984

Kotsantonis, S., Rehnberg, C., Serafeim, G., Ward, B.,

& Tomlinson, B. (2019). The Economic Significance

of Long-Term Plans. Journal of Applied Corporate

Finance, 31(2), 22–33.

Manchiraju, H., & Rajgopal, S. (2017). Does Corporate

Social Responsibility (CSR) Create Shareholder

Value? Evidence from the Indian Companies Act

2013. Journal of Accounting Research, 55(5), 1257–

1300. EconLit.

Meuer, J., Koelbel, J., & Homann, V. H. (2019). On

the Nature of Corporate Sustainability. Organization

& Environment, 1086026619850180. https://doi.

org/10.1177/1086026619850180

Morningstar. (2020). Sustainable Funds Weather

the First Quarter Better Than Conventional Funds.

Morningstar, Inc. https://www.morningstar.com/

articles/976361/sustainable-funds-weather-the-first-

quarter-better-than-conventional-funds

Vishwanathan, P., van Oosterhout, H. (J. ), Heugens,

P. P. M. A. R., Duran, P., & Essen, M. (2019). Strategic

CSR: A Concept Building Meta-Analysis. Journal of

Management Studies, joms.12514. https://doi.org/10/

gf3hq9

Wu, J., Lodorfos, G., Dean, A., & Gioulmpaxiotis,

G. (2017). The Market Performance of Socially

Responsible Investment during Periods of the

Economic Cycle—Illustrated Using the Case of FTSE.

Managerial and Decision Economics, 38(2), 238–251.

https://doi.org/10.1002/mde.2772

Zhang, D., Zhang, Z., & Managi, S. (2019). A

bibliometric analysis on green finance: Current

status, development, and future directions.

Finance Research Letters, 29, 425–430. https://doi.

org/10.1016/j.frl.2019.02.003

19 ESG and Financial Performance

Busch, T., & Friede, G. (2018). The Robustness of

the Corporate Social and Financial Performance

Relation: A Second-Order Meta-Analysis.

Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental

Management, 25(4), 583–608. https://doi.

org/10.1002/csr.1480

Gallardo-Vázquez, D., Barroso-Méndez, M.

J., Pajuelo-Moreno, M. L., & Sánchez-Meca, J.

(2019). Corporate social responsibility disclosure

and performance: A meta-analytic approach.

Sustainability, 11(4), 1115.

Hang, M., Geyer-Klingeberg, J., & Rathgeber, A.

W. (2019). It is merely a matter of time: A meta-

analysis of the causality between environmental

performance and financial performance. Business

Strategy and the Environment, 28(2), 257–273.

Hoobler, J. M., Masterson, C. R., Nkomo, S. M., &

Michel, E. J. (2018). The Business Case for Women

Leaders: Meta-Analysis, Research Critique, and Path

Forward. Journal of Management, 44(6), 2473–2499.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316628643

Hou, M., Liu, H., Fan, P., & Wei, Z. (2016). Does CSR

practice pay o in East Asian firms? A meta-analytic

investigation: APJM APJM. Asia Pacific Journal of

Management, 33(1), 195–228. ProQuest Central.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-015-9431-2

Jeong, S.-H., & Harrison, D. A. (2017). Glass breaking,

strategy making, and value creating: Meta-analytic

outcomes of women as CEOs and TMT members.

Academy of Management Journal, 60(4), 1219–1252.

López-Arceiz, F. J., Bellostas, A. J., & Rivera,

P. (2018). Twenty Years of Research on the

Relationship Between Economic and Social

Performance: A Meta-analysis Approach. Social

Indicators Research, 140(2), 453–484. https://doi.

org/10.1007/s11205-017-1791-1

Lu, L., & Taylor, M. (2015). Which Factors

Moderate the Relationship between Sustainability

Performance and Financial Performance? A Meta-

Analysis Study. Journal of International Accounting

Research, 15, 150320083431001. https://doi.

org/10.2308/jiar-51103

Miras-Rodríguez, M. del M., Carrasco-Gallego, A., &

Escobar-Pérez, B. (2015). Are Socially Responsible

Behaviors Paid O Equally? A Cross-cultural

Analysis. Corporate Social - Responsibility and

Environmental Management, 22(4), 237. ABI/

INFORM Collection.

Plewnia, F., & Guenther, E. (2017). The benefits

of doing good: A meta-analysis of corporate

philanthropy business outcomes and its implications

for management control. Journal of Management

Control, 28(3), 347–376.

Rost, K., & Ehrmann, T. (2017). Reporting Biases

in Empirical Management Research: The Example

of Win-Win Corporate Social Responsibility.

Business and Society, 56(6), 840–888. ProQuest

Central; Sociological Abstracts. https://doi.

org/10.1177/0007650315572858

Vishwanathan, P., van Oosterhout, H. (J. ), Heugens,

P. P. M. A. R., Duran, P., & Essen, M. (2019). Strategic

CSR: A Concept Building Meta-Analysis. Journal of

Management Studies, joms.12514. https://doi.org/10/

gf3hq9

Wang, Q., Dou, J., & Jia, S. (2016). A Meta-Analytic

Review of Corporate Social Responsibility

and Corporate Financial Performance: The

Moderating Eect of Contextual Factors.

Business & Society, 55(8), 1083–1121. https://doi.

org/10.1177/0007650315584317

References for Figure 3: corporate-focused quantitative meta-analyses published since 2015